My enduring curiosity and passion for problem-solving led me to work on a problem that the principal leaders of the Lean movement either ignored or told me that it would be a waste of time. I could not ignore it and I did not see it as a waste of time. My view is that arousing interest in Lean management is irresponsible and disrespectful if people are certain to run into known, nearly immovable structural impediments that make it unable for them to actualize their dreams and contribute in greater ways to both work and society.

The most formidable impediment that we all easily recognize is leadership, but until now there has been only vague and incomplete speculations as to why the leaders of organizations act as impediments to Lean transformation — not just in recent times, but for earlier systems of progressive management as well. Rather than being the least worthy of problems to solve, executive resistance is, of course, the most important problem facing the Lean community. Without a better understanding of the problem, Lean may soon fade away.

For many years I have been carefully studying the problem of executive resistance to Lean management. In two recent works, I have articulated the causes from these perspectives:

Both works have been well-received and have generated much conversation, soul-searching, and new thinking. In this blog post, I present the third and final perspective: Business. (A fourth perspective, psychology/neuroscience, will soon come from others [1, 2] who are knowledgeable in that subject).

The business case used by business leaders to ignore Lean is deceptively simple, and is explained below — with the continuing understanding that what follows merely points out the facts, with no intention to disparage, and to simply illuminate the common state of affairs so that improvement ideas can be generated.

In most of the world, companies operate in a free market, which means it is a competitive market governed by the laws of supply and demand. This is a means of determining prices – a “price-system” – based on the quantity supplied by producers and the quantity demanded by users. Rarely are the two in equilibrium, and for good a reason: Profits. In particular, the gain in profit depending on the price that the market will bear as determined by supply and demand at any given point in time. (Note that “supply and demand” applies to the goods and services a company produces as well as the company itself).

There are certain facts of business thinking and practice that are relevant to the business case for ignoring Lean: Owners and managers very much want to avoid gluts (buyers’ markets), and so they are always angling to achieve sellers’ markets and therefore gain pricing power — in other words, an overwhelming fear of competition. Business leaders are generally distrustful, and specifically distrustful of stakeholders such as suppliers, employees, and competitors — and often their peers as well. They don’t like workers because they can neither be capitalized nor depreciated. Efficiency, productivity, and cost reduction are of interest, but these are best achieved by procuring new machine technologies (machine-based process improvement); there is far less interest in human-based technologies (the brain; ideas and creativity) in large part because technology decides who wins and who loses. Business leaders love economies of scale, more for scale than for economies (though, EoS does amortize waste, which is so much easier to do than eliminate waste). They are self-interested and seek to maximize their own gains, with salesmanship, marketing campaigns, and sales promotions featuring prominently in efforts to maximize gains. They have a zero-sum mindset, where one party’s loss is another party’s gain, and so they always seek to win at someone else’s expense. Winning is paramount for leaders, even if only in appearance, because it confers status, authority, and the right to maintain the status quo — which is why, for example, challenging leaders to adopt Lean management or practice Lean methods and tools, usually fails. They believe a business must “grow or die,” which is actually a statement about the importance of gaining leverage over other stakeholders, to win. They love dealmaking and are always on the hunt for mergers and acquisitions. The “synergies” (cost savings) that help sell the deal rarely materialize because they are not important. The bigger the company (scale), the more it is able to “buy cheap and sell dear;” to gain market power in order to exert leverage over suppliers to obtain low prices and leverage over customers to obtain high prices, and generally to gain tangible and intangible concessions from any party that the company interacts with.

Business is the pursuit of profit (gain) “with the frame of mind that is native to the countinghouse.” Managers are required to produce a profit, free income, which is embedded in price as well as determined by price. Therefore, there is an incentive to withhold supply to achieve a sellers’ market and gain pricing power. But, as demand varies over time, supply must be throttled to avoid overproduction and the creation of a buyers’ market. The ability to throttle output is of supreme importance and is aided by economies of scale (and sales incentives), which greatly extends the range of available throttling positions and price points. In other words, the cost savings achievable with economies of scale is of less importance than the number of price points and price increases that are achievable.

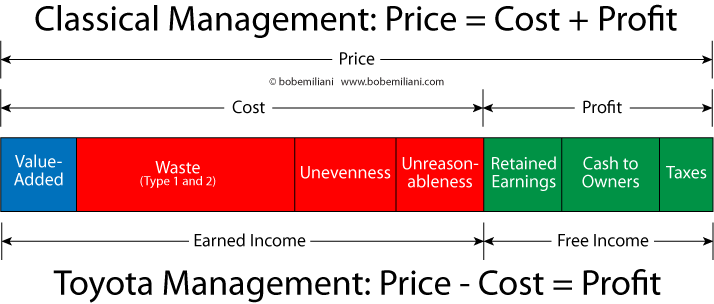

The image below shows the view of price, cost, and profit for Classical management and for Toyota management. Importantly, it shows the breakdown of cost as the sum of value-added plus waste plus unevenness plus unreasonableness, and profit as the sum of retained earnings plus cash distributed to shareholders plus taxes. When a product or service is sold, the producer earns income (cost of production) plus free income (profit). Price, cost, and profit are all important parameters. But which do managers focus more on, and why?

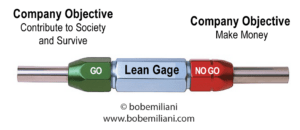

When a company’s objective is to make money (Classical management), management’s focus is on prices. Specifically, increasing unit prices to gain more free income (profit; i.e. wealth). Waste, unevenness, and unreasonableness raise both market prices and profit (as a percent of cost) — with prices having been set by managers. Greater mismatches in supply and demand, especially those which favor the producer (and which generate greater amounts of waste, unevenness, and unreasonableness), result in higher prices for customers. Working to obtain a sellers’ market — by mergers and acquisitions, patents, economies of scale, monopoly, or other methods — means there is little or no need to eliminate waste, unevenness, and unreasonableness. The existence of waste, unevenness, and unreasonableness is beneficial in terms of higher prices; it is a desirable feature of Classical management, not a flaw. It standardizes, legitimizes, and normalizes CEOs’ use of the Wealth Creation Playbook. In Classical management practice, waste, unevenness, and unreasonableness helps business leaders run the business more successfully in a market economy, always in the short-term because of the ever-fluctuating nature of supply and demand. They use the market economy to their advantage. The fact that companies often overproduce (or destroy wealth) does not alter business leaders’ underlying logic for ignoring Lean, because overproduction can provide tactical wins in pursuit of larger strategic wins.

When a company’s objective is to contribute to society and survive (Toyota management), while gaining free income (profit), then management’s focus is on reducing total costs by eliminating waste, unevenness, and unreasonableness to lower market prices while helping to obtain more profit — with prices having been set by customers. A closer match between producer’s supply and customers’ demand results in fair prices for customers. Toyota must operate in a market economy, just like every other business, so some of its practices bend towards Classical management (such as sales promotions), or a desire to keep supply tight to avoid too much discounting or brand (or model) erosion. Such is the reality, which results in compromise — at least until better solutions can be found.

Fundamentally, Classical management operating in a market economy is driven to pursue a profitable price. Toyota management, also operating in a market economy, is driven to pursue satisfying the material wants and needs of the members of society. In Classical management, business leaders have no interest in the product, processes, or people; only that the price is profitable. It is the opposite for Toyota management, and presumably true for Lean management as well, recognizing that profits are akin to human nutrition (food energy), whereas loan credit, used liberally in Classical management, is akin to steroids (artificially boosting performance) to gain the upper hand.

And finally, it is important to recognize that survival was a primary reason for the creation of the Toyota Production System and The Toyota Way. If management has no interest in the business surviving, meaning it viewed merely as a (private) property that can be sold, merged, or liquidated at any time – whichever is more profitable – then the raison d’etre for pursuing Lean management disappears. And since a business is property, executive teams seek to increase enterprise value, and in doing so they choose the simplest means possible: the Wealth Creation Playbook, not Lean.

This articulation of the business case for managers ignoring Lean completes the trilogy that I sought to present to the Lean community and Lean movement leaders. I hope that you find my work illuminating, and I encourage you to read my two earlier works, Triumph of Classical Management over Lean Management and “The Business Philosophy Triangle.”

With these three works, the big questions that have long plagued Lean management, and as well as earlier forms of progressive management, have finally been answered. In them, you will also find a narrowing of problems that led me to offer some countermeasures. And I trust that you are able to think of others.