In previous work, I explained in extraordinary detail why leaders resist or reject Lean management. Unfortunately, leaders will never explain their dislike for Lean as I described it because it gives away too many of their deepest secrets. Instead, they will justify their dislike for Lean using three rudimentary, if not simplistic, macro-level arguments: Jeopardy, Perversion, and Futility. These powerful arguments are put forward to conserve the current state; to preserve the status quo by fending off progressive thinking and practices; to put Lean into arrears and, eventually, discredit it. These arguments have existed for centuries. They remain useful because it produces the desired results — to slow down change, stop change, or even go backwards. Lean people should understand these overused arguments so they can refute them and be aware of traps that they may inadvertently set for themselves when they proffer counterarguments.

It is important to recognize that both the allies and enemies of Lean are good people putting forth arguments that align with their deepest personal and work-related beliefs. Their arguments reflect reality as they see it, though not necessarily unbiased or untainted by cynicism or free ulterior motives. One thing to consider as you read this post is that if Lean was seen as a large threat by business leaders, you would see the Jeopardy, Perversion, and Futility arguments fully, forcefully, and consistently deployed by CEOs, politicians, conservative think tanks, etc., in the media and elsewhere.

The fact that these arguments remain somewhat weak and limited shows that Lean management is not yet seen as a significant threat to those in power and the normative order of leadership and business. For over 30 years, CEOs have been able to very effectively control the intrusion of Lean management into classical management by limiting its influence to some tools they require lower level employees to use — and thus retarding the advancement of leadership and management practice.

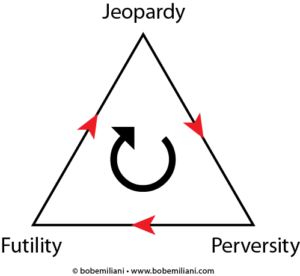

The three arguments, which you are no doubt familiar with to some degree, follow a logical sequence in their deployment by those who are hostile to change and improvement. While the arguments are rudimentary, they are highly effective and can be deployed ad infinitum, drawn upon whenever needed, as shown by the circular arrow in the above image.

It begins with Jeopardy, which is a prediction that bad things will happen if Lean management replaces classical management. The amount of harm is always exaggerated for greater effect. Next comes the Perversity argument, which comes from observation, where change has resulted in outcomes that are opposite of what was intended. Lastly, the Futility argument, whose formulation is based on the production results over a long period of time, argues that no real change has been achieved despite great effort, and so there is no point in continuing further to seek ameliorative change. The three arguments effectively utilize skepticism and sarcasm as effective rhetorical devices.

Jeopardy Argument: Lean transformation is a leap that will bring disastrous consequences or will in some way change things for the worse instead of for the better. While these deductive arguments are entirely speculative, they carry great weight because of the consequences that failure can bring. Lean transformation, lacking cookbook standardization, is filled with many different types of risk — especially when unskilled managers lead the transformation — and so the likelihood of many failures large and small is high. In classical management, people get blamed for problems. Thus, problems are to be avoided if one hopes to remain employed or advance within the hierarchy. A familiar prediction is how improvements in production will upset downstream processes such as the ability to grow sales or satisfy customer demand; essentially, “we will lose more than we gain.” Other familiar predictions include Lean transformation will cost too much, it will take too long, and it will endanger previous accomplishment or recent gains in performance. Managers will say “the time is not right,” “we are not ready for Lean,” “we’re too busy,” or “Lean is old and no longer relevant.” Workers will join in the predictions and say that Lean will dehumanize them, speed them up, and burn them out, take away their knowledge and creative, and cost them their job.

Perversity Argument: Lean transformation made existing conditions worse — Lean backfired. Rather than being a remedy to improve, it was injurious to the current ways of doing things. A recent example that has been extensively reported in the business press pertains to Just-in-Time. JIT “inventory management practices” failed when needed most during the COVID-19 crisis. It is irrelevant that reporters do not understand JIT, that the stories are inaccurate and misleading, and that most business leaders misunderstand JIT, or that most companies practice JIT incorrectly. Rather than determine the root causes of these problems, the only clear and sensible solution is to shift from JIT “inventory management practices” to “stockpiling months, rather than weeks” of material. This creates new demand for additional warehouse and distribution capacity which other businesses, following the innately correct logic of their customers, are delighted to satisfy. You have probably witnessed or heard of many other examples where Lean management went wrong and caused various forms of confusion, errors, delays, and re-work — a singular or chain of unintended consequences contrary to the goals of Lean — made matters worse. Lean’s perverse effect is “change for the worse,” rather than “change for the better, which in this argument is seen as predictable.

Futility Argument: Lean management failed to deliver the promised improvements. There are few examples of Lean transformation and very few leaders who have led Lean transformations. The best that Lean could do was produce some cosmetic changes while the underlying systems and ways of thinking and doing things remain largely, if not wholly, unchanged. Hence the negatively biased epigram “the more things change, the more they stay the same” (attributed to Jean-Baptiste Alphonse Karr in 1849: “Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose“). Relatedly, the phrase often repeated by Art Byrne that “everything must change” when it comes to Lean transformation may do more to assure that everything stays the same than is realized — a perverse effect, to be sure, one that reinforces both the futility and jeopardy arguments. So, what looks like change is not, in fact, the deep change as sought by the proponents of transforming the practice of management from classical to Lean. Lean proponents seek to elevate workers and make use of their knowledge and creativity to develop themselves and advance the interests of the company, yet the highly structured normative order of leadership and business is driven to ensure that workers (majority) cannot disturb the power, rights, privileges, and decision-making authority of leaders (minority). Leaders’ continued dominance and disdain for relinquishing any power renders Lean transformation futile. You may recall in years past examples of large companies whose best, most productive manufacturing plants were closed. This demoralizes people and causes them to ask: “It is even worth trying?”

One can see that these three arguments are based on speculation and selective use of evidence to subvert efforts to alter the status quo – in essence, they are political arguments. What can be done to refute these arguments? Chances are we will make the same three simplistic arguments but from the opposite direction and likely trap ourselves into a stalemate. These opposing arguments utilize certainty and moral indignation as ineffective rhetorical devices, and may be expressed as follows:

Jeopardy Argument: The future is grim. Continuing to do things as they have always been done will make things worse. Lean will strengthen, not weaken, business and society. The company will be more competitive and survive. Lean will save the company. Lean will repair and invigorate capitalism. If you don’t adopt Lean, the consequences will be disastrous. Things will not improve if we don’t try. Inaction carries great danger.

Perversity Argument: We have seen the results. The way things have been done in the past yield uneven outcomes for people; there are too many losers. Economic preconceptions serve the rich. Globalization backfired. Workers are asked to think but they are rewarded only for doing. Employees have become alienated from their work and their employers. Classical management has failed and must be replaced from the ground up.

Futility Argument: Classical management cannot be improved. It delivers only for shareholders and not for stakeholders. Stakeholder capitalism cannot function under classical management — instead it requires Lean management. Bad things will keep happening if we do not embrace change. We cannot keep up with the times when things remain the same. The status quo cannot compete with evolution and humanity’s desire for change.

The likely effect of these counterarguments is… no change. The opposing arguments cancel each other out, but easily favor those aligned with the status quo (i.e. the current state; those with power). So what should a Lean person do to confront the three arguments made against Lean transformation? From Toyota and their practice of kaizen we learn a way of thinking about problems that can perhaps erode or blunt — but not defeat — these arguments:

Jeopardy Argument: The cost of Lean transformation outweighs its benefits. Counterargument: These are predictions. Stop making predictions. Don’t brainstorm. Instead, try it out for yourself and see.

Perversity Argument: Lean transformation produced the opposite results. Counterargument: You tried it out and it did not work. Don’t give up. Try again. Keep on trying. Continuously improve your methods to achieve the intended results.

Futility Argument: Lean transformation failed to produce the intended result. Counterargument: This is a fallacious argument based on feelings, not on the facts. Feelings can be amended, and confirmation bias can be overcome.

These counterarguments will be more forceful if one is a position of power, which often is not the case. Furthermore, the three arguments against Lean transformation are premised on the high value attributed to the normative order of leadership and business as seen by CEOs, politicians, and society. When this premise falters, there will be a huge opening for widespread Lean transformation. But that could be far into the future.

Until then, it seems the only option is to muddle along. But perhaps not. An alternate path may be for leaders and followers to negotiate a practical solution that brings changes that are acceptable to both parties. (What would precipitate such good-faith negotiation is unknown). I proposed a negotiated solution in my book, The Triumph of Classical Management Over Lean Management: How Tradition Prevails and What to Do About It. It is called iMaP — Improved Management Practice — whose intent is to get both parties to agree on a small set of changes designed to be mutually beneficial. Perhaps that can be a productive way forward in the evolution of progressive management.