A professor asked the following question:

“One of the items that stands out from your writing is the need for leadership. Given the (at best) lukewarm reception so far for Lean in higher education, the question is: What are we doing wrong? Why are we failing to engage colleagues and administrators? What different strategies could be used to close generate more interest?

It’s not that we are doing anything “wrong,” but we do indeed have difficulty engaging colleagues and administrators. Let’s begin with leadership engagement in Lean management. This remains a huge challenge because it is so far afield of leaders’ educational background and higher education work experience. And, there are shiny new things like learning management systems and online courses that compete with it. These new technologies require little from leaders. Lean, on the other hand, requires higher ed leaders to learn many new things – new ways of thinking and doing things – that turns them off. So, they delegate Lean implementation to lower level people. They think they are being wise leaders by doing that. Instead, they are being unwise managers. By delegating Lean, they guarantee successes will be few, slow to come by, and limited in scope – or that Lean fails.

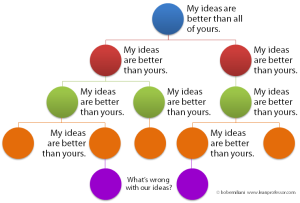

I have written extensively about the problem of engaging leaders in private industry. Higher education is different in some ways, and I have provided guidance in two my books and journal papers. A main distinction between private industry and higher education is that the former is top-down, while the latter is an environment of (mostly) shared governance. Nevertheless, people in high positions tend to have a common trait: They think their thoughts and ideas are better than people lower down in the organization – a faulty mindset that Lean management seeks to break. Short of gemba kaizen training, it is difficult to break this mindset among top university leaders.

I have written extensively about the problem of engaging leaders in private industry. Higher education is different in some ways, and I have provided guidance in two my books and journal papers. A main distinction between private industry and higher education is that the former is top-down, while the latter is an environment of (mostly) shared governance. Nevertheless, people in high positions tend to have a common trait: They think their thoughts and ideas are better than people lower down in the organization – a faulty mindset that Lean management seeks to break. Short of gemba kaizen training, it is difficult to break this mindset among top university leaders.

Looking at this another way, we could say that higher education leaders lack the “spirit of change.” Instead, they are committed to the “spirit of same.” This is disturbing because one expects leaders to help people move forward as time goes by, to reduce risk to the university and one’s livelihood. If leaders do not do that, they they are failing in their primary job of leading people. In other words, leaders serve no useful purpose for followers if they do not help followers improve and adjust to changing circumstances. Leaders who allowing time to pass with no process improvement are irresponsible.

Leaders are important because they play a critical role in keeping followers focused on the fundamentals, much in the way that sports coaches do for athletes. Leaders, as well as followers, think they have “mastered the basics” when they have not. How do we know? There are too many recurring administrative and teaching errors. Leaders make hundreds of mistakes in how they lead people and manage the university, and teachers make dozens of mistakes in teaching students. A professional is someone who makes few mistakes.

Kaizen teaches that you must always focus on the basics, so that you make few errors and to help you clearly see what needs to be improved. As sensei Nakao says, “To make good product, you have to make good people,” meaning that leaders have to develop people to embrace “the spirit of change.” Followers – staff and faculty – lack “the spirit of change” because their leaders do too.

Problems abound, big and small, that should garner the attention of leaders, but often they don’t. Sensei Nakao taught us to take immediate action irrespective of the size of the problem. He says: “Kaizen means taking action; go to the genba, now; deal with the facts, now. Always take action; that is the key.” It requires strong, tenacious leaders who lead by doing rather than by talking. Leaders who ignore problems and who do not take action are irresponsible.

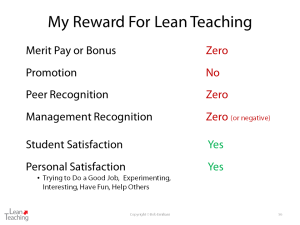

When it comes to one’s colleagues, I have found difficulty there too. One reason, it seems, is that the reward system in higher education discourages divergence from the norm. Logical arguments for continuous improvement are empty when rewards support the status quo, or when student course feedback is largely ignored by administrators. In addition, faculty tend to act as independent contractors, each pursuing their own goals, and not as team members. The slide at right shows what I perceive to be my rewards for Lean teaching since around 1999. How many faculty want a couple of intrinsic rewards and mostly zero extrinsic rewards?

When it comes to one’s colleagues, I have found difficulty there too. One reason, it seems, is that the reward system in higher education discourages divergence from the norm. Logical arguments for continuous improvement are empty when rewards support the status quo, or when student course feedback is largely ignored by administrators. In addition, faculty tend to act as independent contractors, each pursuing their own goals, and not as team members. The slide at right shows what I perceive to be my rewards for Lean teaching since around 1999. How many faculty want a couple of intrinsic rewards and mostly zero extrinsic rewards?

So what can be done? Firstly, there is not one solution to the problem of engaging our colleagues and administrators. A lot of things must be done in combination, over a long time, to generate interest in something for which there is often no extrinsic reward for knowing about or doing. We just have to be persistent and creative, because we know Lean management – done right – is better for students both in and out of the classroom.

The main strategy that people use to engage their leaders or faculty is information sharing and education:

- Give presentations to show the opportunity and to generate interest

- Give them papers, reports, or books to read

- Have them talk to people who have Lean higher education experience

- Visit universities that are making some progress

- Get them to attend a Lean higher ed conference

- Get them to commit to attend Lean training

This may be more effective for faculty and staff, who are closer to students. But it has a limited effect among leaders because, being leaders, they can choose to ignore the facts. Leaders who ignore facts are irresponsible. Perhaps it all boils down to finding responsible leaders – people who will not allow time to pass without process improvement, who will not ignore problems, and who will not ignore facts. That specific challenge falls to search committees and to college and university trustees, boards of regents, etc., just as it does in private industry. Faculty will follow good leaders – leaders who lead by doing rather than by talking.

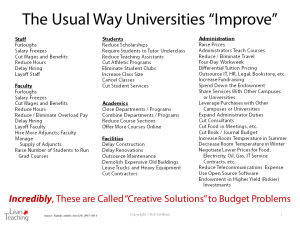

My view, however, is that if top college or university leaders think everything is fine and do not see problems, both large and small, then “the spirit of change” will not exist. Change will be limited to doing the same things that the herd is doing (see image at right). There’s no leadership in that. But, remarkably, there is good money in following the herd and creating the façade of strong and insightful leadership.