The late 1970s and 1980s were an exciting time for those who studied Toyota’s production system and Japanese management practices. Authors such as Monden, Cusumano, Schonberger, Suzaki, Hall, Imai, Womack, Jones, Fujimoto, and others — particularly the great Norman Bodek (1932-2020) who published classic works by Ohno, Shingo, Sekine, Hirano, and others that will forever remain useful (and who in recent years wrote several interesting books). These people brought us substantial works of practical scholarship that inspired a generation of people to think and practice management differently. They were the thought leaders and we waited anxiously for their next words.

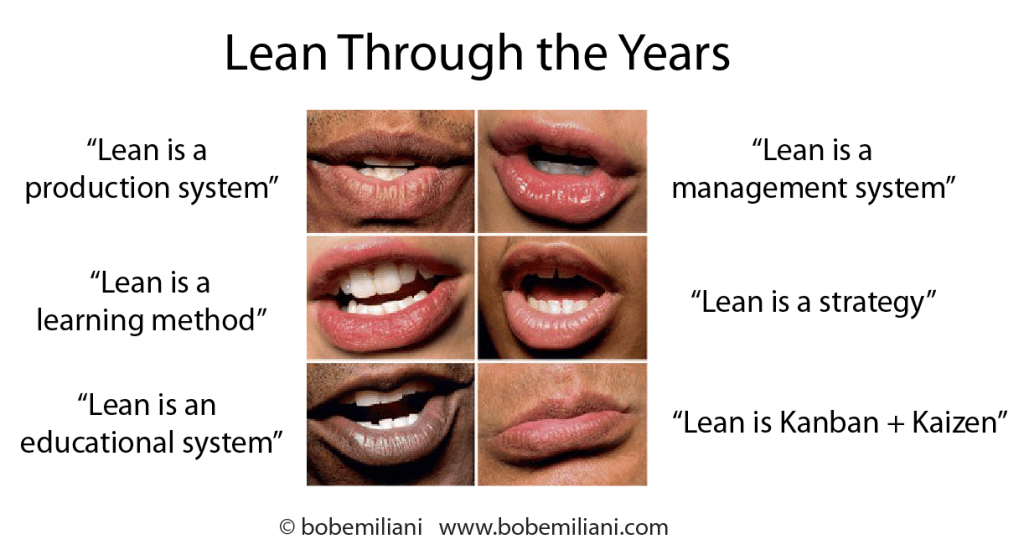

But times have changed. In recent years, we have drifted from thought leadership to banal thoughts. This is most obvious on social media where varied luminaries express some view or another about what Lean is, what Lean isn’t, what Lean was, or what Lean should be. No doubt their intent is wholesome — to gain new followers, energize existing followers, and to advance the practice of Lean management — though perhaps a bit self-serving (there is no great sin in that). Banality is ever-present today in most organizations as well, given the great influence of people inside and out whose understanding and practice of Lean remains simplistic and substantially based on slogans or that which is fashionable at a given point in time.

Some years ago, the credit card company Visa used this slogan: “It’s Everywhere You Want to Be.” Today’s Lean slogan is: “It’s Everything You Want It to Be.” What would Taiichi Ohno think of that?

Most books — not all — written about Lean and TPS over the past 10 to 15 years are largely repetitions of what was published in the 25 to 30 years prior. These hagiographic works scrupulously avoid insightful analysis and penetrating criticism and make their mark solely as reverential works. Today, people who have been in this field a while find little that is worth reading because it lacks originality. Such works may be useful to newcomers, but if they are serious students of TPS and Lean they will seek out original sources and find them to be much better in almost every way.

Banalities reflect the current unhealthy state of Lean. Lean is reduced to simplifications that, while perhaps true, stand as empty communications. The banality of Lean means it no longer feeds the brain as it once did. And it no longer inspires the practice that it once did. Lean seems intellectually exhausted. It may be spent in practical terms as well given its truncated application in most organizations. The consequence of banality is a loss of creativity and innovation through the ceaseless repetition of common bromides which propel clumsy or ill-informed practice. It calls to mind the circle of life, from birth to survival to death. For Lean, it is the life cycle of a product, one that seems better poised for renewal than the continued use of its various remnants.

We constantly hear the phrase “No problem is a problem.” This too has been reduced to a banality given the propensity for ignoring problems that banality demands.