“In music, a standard is a tune or song of established popularity” among listeners. In business, a standard is a decision of established popularity among leaders. Namely, raising prices without improving value for buyers. It is a standard decision among leaders because it results in more money with no extra effort. But good things like that do not last long.

This week, there was an interesting article in Times Higher Education that speaks to smart leaders making dumb decisions, titled “More English students think degree was poor value for money. Since the UK higher education authorities instituted a £9000 tuition fee cap in 2012, “The proportion of English undergraduates telling a major survey that their degree was poor value for money has exceeded the proportion who felt it was good value for the first time.”

The increase in dissatisfaction is dramatic, nearly a doubling in just 4 years. Undergraduate students cited low faculty-student contact hours and delays in returning assignments as major dissatisfiers. Surely there are many more dissatisfiers than just those two, and tuition payers cannot be happy either.

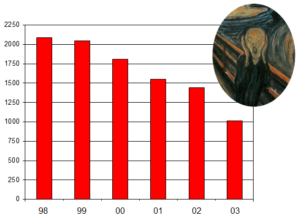

This reminds me of the time when I taught a Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (Hartford, Conn., campus), wherein the president, Shirley Ann Jackson, and the provost, Bud Peterson, doubled tuition per credit hour with no corresponding improvement in value proposition. The result was a 50 percent decline in enrollment. This, in turn, led to a voluntary exodus of faculty and non-renewal of faculty contracts. When I started at Rensselaer in 1999, there were 35 full- and part-time faculty in the management school. When I left voluntarily in 2005 there were 12. Enrollment stabilized until about 2010, and then continued its decline to zero. The management school closed this year.

Our satellite campus and main campus leadership was deaf, dumb, and blind when it came to student (and faculty and staff feedback). But we also failed in our responsibilities as educators. In many cases the teaching was lackluster, the teaching materials were aged or not relevant, course materials or topic overlapped, some faculty were condescending to students, response to student course evaluation were uneven, assignments were returned weeks later, there were course scheduling problems, and so on. In short, we – administration, faculty, and staff – mismanaged the face-to-face learning experience. So our students fled in search of better and lower-cost learning experiences, of which there were many good schools in the area to choose from. I’ll bet the same situation, more or less, exists in the U.K. today.

We faculty did not sit still and do nothing. Among the actions taken were to kaizen our premier executive master’s degree program in 2002-2003. This is described in my book Lean University and in my paper “Using kaizen to improve graduate business school degree programs.” While we were successful, it was too late. It did not help that top university administrators did not see merit in our wonderful kaizen results.

The Times Higher Education article says:

“…the survey also reveals a significant gap between many students’ expectations of how long it should take for their assignments to be marked and returned. While students’ expectations were met or exceeded in 54 per cent of cases, they were not in 46 per cent, and there were several disciplines – communications, business and education – where they were not met in the majority.

Forty-three per cent of students felt that it would be reasonable to receive their assignments back within a fortnight, but this happened in only 22 per cent of cases. A quarter of students said that it took up to four weeks to get their work back – a situation that only 12 per cent found acceptable.”

I return assignments to my students the day after they are submitted. I started doing that sixteen years ago. It was apparent then that students did not want to wait to get their assignments back, as circumstances had changed compared to the 1960s, 1970s, or 1980s. The long delay between assignment submission and feedback was long known to be major dissatisfier, but few faculty bothered to construct new, more focused assignments, that could be evaluated quickly and returned to students overnight (for more on that, see my book Lean Teaching).

Another article in Times Higher Education makes a call for change: “If you are not updating your lectures, you could be letting your students down.” Could be? No, you are for sure letting your students down.

Smart leaders can easily make dumb decisions that result in a lowering of the value proposition, which, in turn, causes students to recognize that they have options which they must carefully examine. As enrollments suffer, the only known course of action known by smart leaders is to make more dumb decisions: to lay off faculty and staff, which further lowers the value proposition for students and payers.

At some point, one has to seriously question (as I did in 2005) the standard for college and university leadership that we have come to accept. It is clearly not adequate for current or future times.