For more than 30 years, CEOs have claimed that wages for workers are too high. American CEOs were the first apprehend and exploit this claim followed by CEOs in most other countries. Is this true? Are wages too high? Consider that Western-style business is normally conducted under the doctrine of force and fraud (where “force” means mandatory, compulsory, or coercive and “fraud” means non-criminal deceit and trickery). Examples of force include:

- Wage and benefits cuts for all non-executive employees, and involuntary layoffs even when business is good

- Demanding price cuts from suppliers or risk losing the business

- Reducing the quality or quantity of goods and services to customers

- Demands for tax cuts from communities for the business to not move to a more favorable domestic or international location

Fraud can be misleading investors or failing to the contractually agreed-upon number of jobs in exchange for government tax breaks. Our focus here is the deception that there is no money for higher wages or better benefits for non-executive employees; that these are already too high and must be cut. Fraud is the trickery that people will not question what CEOs say. Non-executive employees, the business press, politicians (who always talk about jobs and job creation), and many others take it on faith that leaders are honest and that they have the required factual information to make the claim that wages are too high. Big mistake.

Yet, there is always money for mergers and acquisitions, with CEOs invariably paying much more than the entity is worth. These overpriced deals reflect CEOs deep-rooted preference for cowardly conquest over courageous and fair competition. There is always money for higher executive pay and benefits, where payment is guaranteed, or virtually guaranteed, regardless of business performance or market conditions. There is always money for higher dividends — borrowed money, if needed, so that shareholders are appeased no matter how poorly the business performs. There is always money for share buy-backs. There is always money for technologies that replace labor. There is always money to pay the costs of involuntary termination and voluntary separation. There is always money for lobbying government officials. And there is always money to pay attorneys and those harmed by defective products or services.

For a large corporation, $25 million is not a lot of money. Some CEOs make multiples of that in a single year. Think about this: $25 million could give a five percent raise to 10,000 employees making $50,000 per year. Leadership is expensive. Do you get what you are pay for? In most cases, no, not to mention the high pay for creating disasters such as Wells Fargo fraud, Equifax data breach, GM faulty ignition switch, Morandi bridge failure, Vale mining disaster, defective Takata airbags, the Boeing 737 Max, etc. Cost exceeds value by a wide margin, even under the best of circumstances — and especially when the route to wealth creation under classical management consists of doing the same simple things over and over again — what I call the CEO playbook.

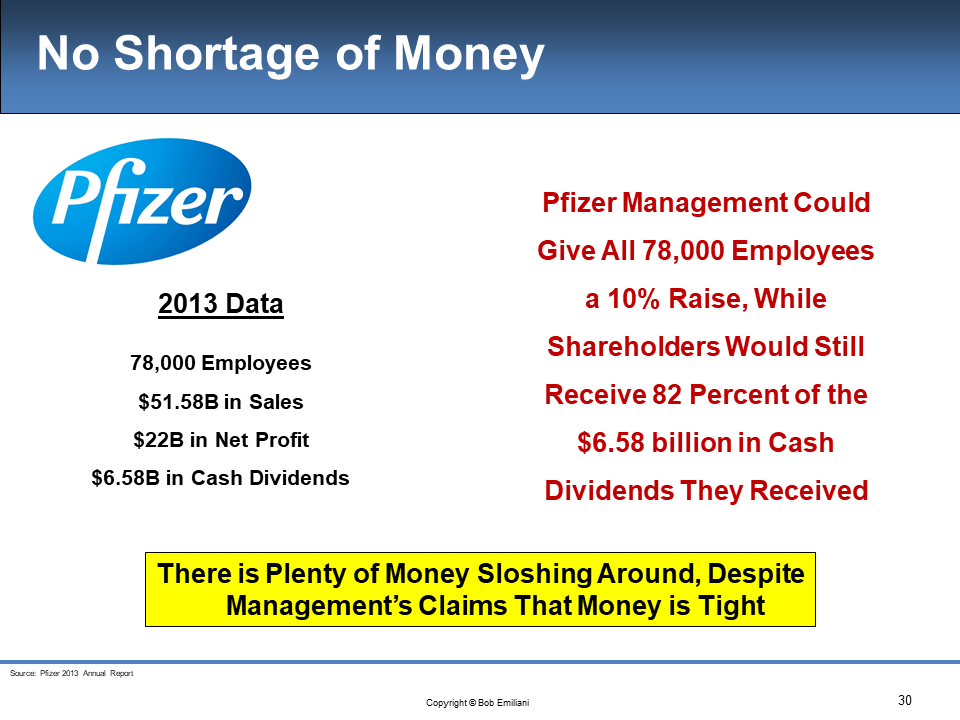

The image below is a lecture slide from 2013 that I presented to students in my Lean leadership course. It shows two things: 1) that shareholders are not appreciably impacted by giving all employees a substantial raise and 2) and that CEOs claims of corporate poverty must be closely scrutinized. By the way, the Pfizer CEO that year said there was no money for raises.

Clearly, there is a lot of money sloshing around — except for workers. Leaders have no desire to increase wages and benefits for non-executive employees. Despite gains in productivity, doing what the boss askes, and having to live with the fear that they may be terminated for any time and for any reason, they do not deserve more money. Workers in manufacturing and service industries have been particularly hard-hit by this multi-decade fraud. The result is social, political, and economic instability. Nice work guys. Yet another penny-wise, pound-foolish decision spanning generations of senior leaders, all because of a preconception that, one way or another, “dead wood” workers the true source of all problems and must be rooted out. By way of inference, there can be no such thing as “dead wood” CEOs.

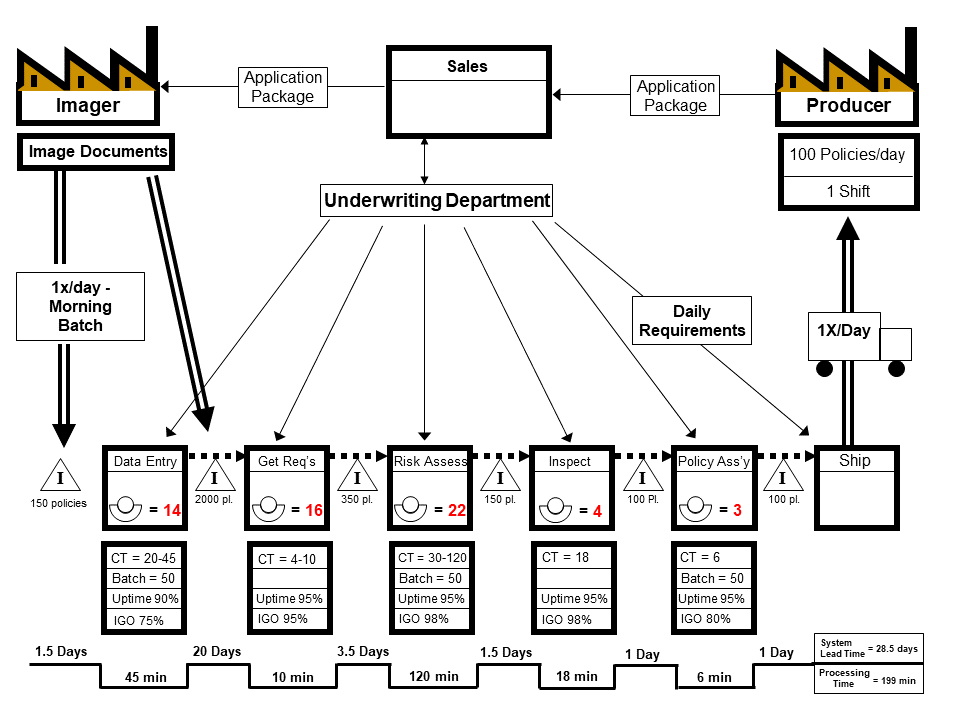

Back in the late 1990s and early 2000s, value stream maps were supposed to be a revelation to senior executives. It showed them that current state processes were very bad, consisting of many steps, confusing information, unbalanced cycle times, big batches, large amounts of work-in-process, etc., and weeks of lead-time to do only a few minutes of value-creating work. The process needs to be improved under their deft leadership. Banishing waste would create wealth, so the thinking went. But senior leaders did not see any of that.

Senior leaders ignored what they were asked to see and instead saw what they wanted to see: labor was the waste that needed to be eliminated, not process waste as Taiichi Ohno defined it and as James Womack and Dan Jones expounded upon it. Large numbers of workers engaged in processes represented a massive, multi-year opportunity to increase shareholder value. To senior leaders, labor is always the problem. Value stream maps pinpointed the labor problem with great precision so that CEOs could replace in-house labor with automation, outsourcing, and offshoring to quickly increase the stock price and, in turn, increase stock option-based executive pay — and depress the wages of those workers who remain.

Value stream maps backfired in a big way — perhaps all of Lean as well. It turbocharged what leaders learn in business school and on-the-job: convert fixed costs to variable costs. Who has time for or interest in improving processes? It is much more economically efficient to destroy internal processes and outsource them to suppliers who can be perpetually bargained with to obtain lower prices. If the current supplier does not capitulate to their customer’s demands for lower prices, there are always many other suppliers who will do the work.

No case can be made that wages are too high given that wages have been depressed for more than 30 years, as evidenced by the gap between productivity and pay, inflation, shrinking workforce, etc. My salary as a professor in public higher education has kept up with inflation. What I earn today is virtually the same as what I earned when I joined Pratt & Whitney after I completed my Ph.D. in 1988. My colleagues and I are fortunate because so many other people’s wages has not kept up with inflation.

This positive result is made possible by a labor union representing university instructors. Unfortunately, there is a widespread and deep-rooted negative perception of labor unions, even among wage earners, such that union influence and membership remains in a state of continuous decline. There are some things I don’t like about my labor union, but I have been better off with them than without them. Unions bust force and fraud. If not them, then who?