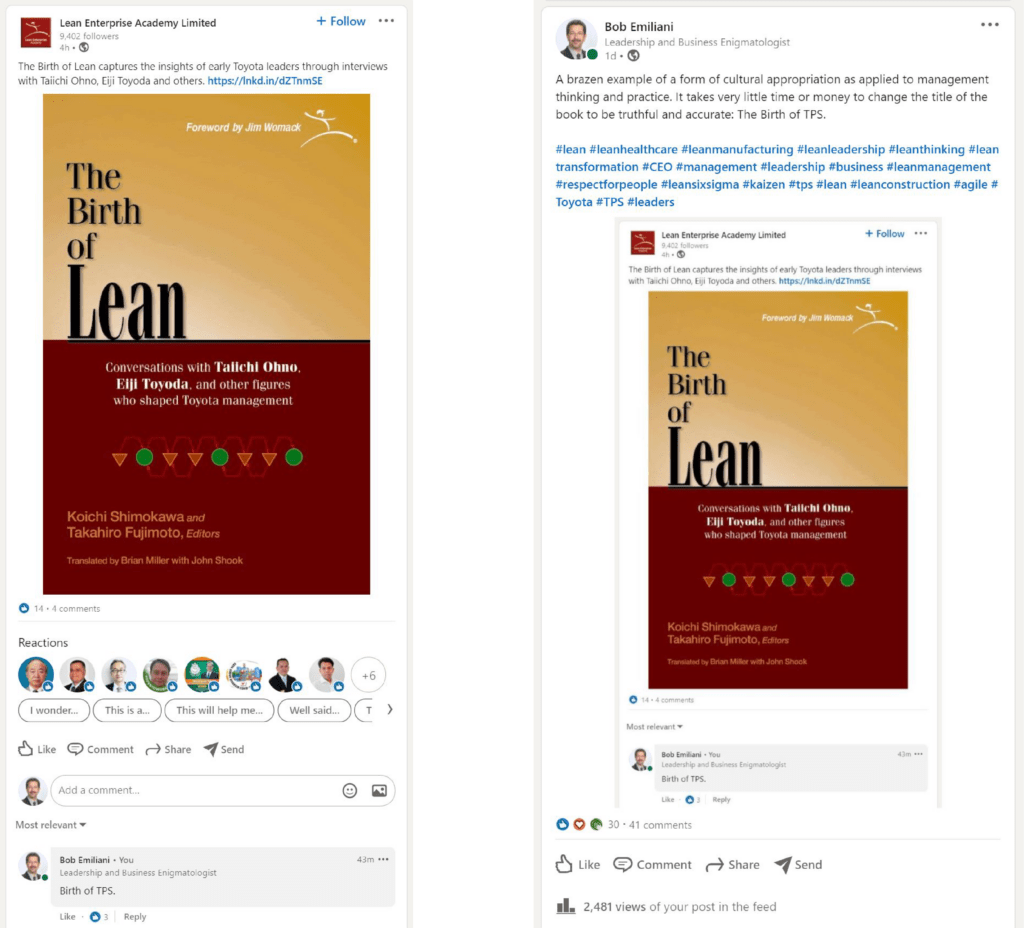

On 14 July 2021, The Lean Enterprise Academy (LEA) posted the image shown below (left side) on LinkedIn. My comment to the post was: “Birth of TPS.” Meaning, the title of the book, The Birth of Lean was incorrect. Many people agreed with (“Liked”) my comment, which is historically and factually correct based on the content of the book.

LEA countered with the comment: “The book title is correct and shouldn’t be changed.” I replied: “The book title is obviously incorrect and should be changed. It is both historically and factually inaccurate. Toyota did not give birth to Lean. Lean (ca.1988) came after the creation of TPS (ca. 1973). Lean and TPS are not the same thing, despite your protestations. The ethical thing to do would be to change the title and not mislead your customers. It’s not difficult to do the right thing.”

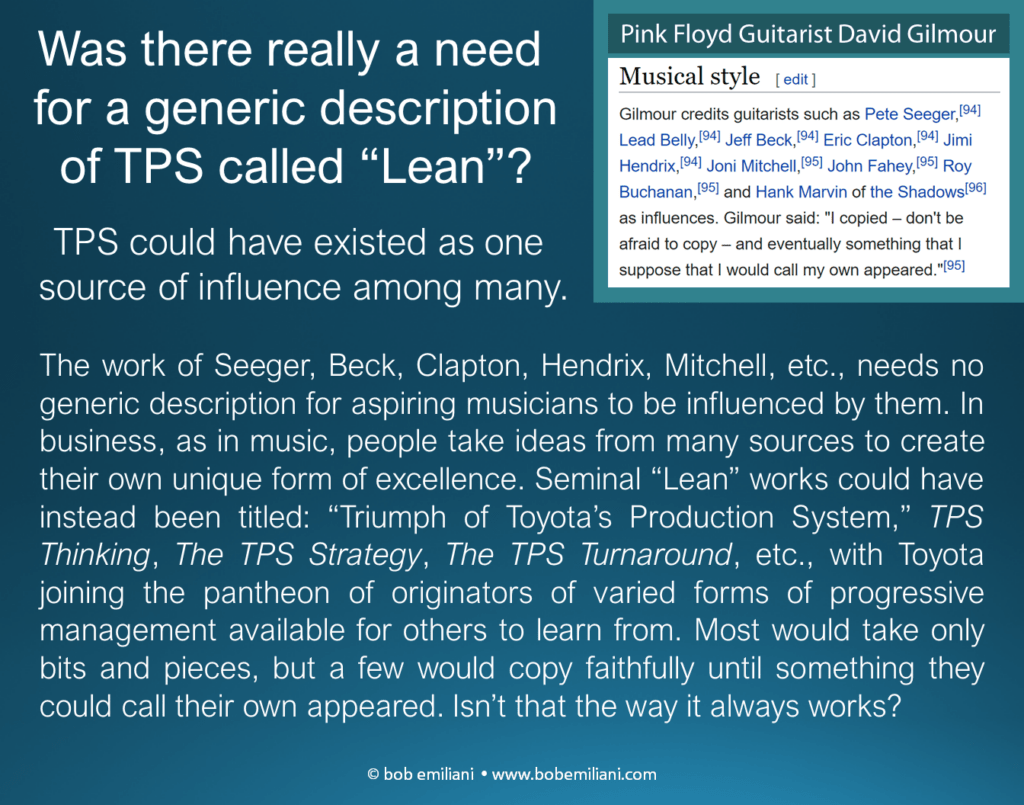

The term “Lean” was birthed by White researchers at Massachusetts Institute of Technology studying — discovering — Toyota’s production system in the mid-to-late 1980s (see the 1990 book The Machine That Changed the World, pages 4-6), and thus came years after Toyota’s Production system was fully developed. A simple, yet inconvenient fact.

Another inconvenient fact is that the book The Birth of Lean is an English republication of a 2001 Japanese edition titled The Origin of the Toyota System by Koichi Shimokawa and Takahiro Fujimoto. Why did the title change for the English edition? Presumably for commercial purposes.

Later that day I posted on LinkedIn the image shown on the right, in which I specifically called out the book title as an example of cultural appropriation and suggested that the book title should be changed to be both accurate and to avoid misleading readers.

At one time (late 1980s to around 2000) “Lean,” was meant to be a generic term for Toyota’s Production system. Lean, being a Western derivative (simplified) interpretation of Toyota’s production system. But post-2000, the creators of Lean began to promote Lean as being equivalent to TPS and Toyota’s overall management system. The lines between Lean and TPS became blurred, perhaps intentionally — if so, a disingenuous and misleading rebranding of Lean as TPS, not for the benefit of customers, but for the benefit of the business of Lean and its most prominent promoters. However, TPS and Lean are not the same, in part because much gets lost in translation from Japanese to English.

The book title, The Birth of Lean, seems to be a clear example of cultural appropriation — a co-opting of TPS and Toyota’s management system made less foreign and thus more suitable to a Western audience. As is the book title Toyota Kata. This begs the larger question of whether Lean management itself is cultural appropriation, and whether the significant changes in the mindset and meaning of TPS has led to anything more useful or more beneficial.

I have been part of the community seeking to inform people about progressive management and to profit from Lean and Toyota’s management system, having at one time being misled into thinking Lean and TPS were the same. While Toyota Motor Corporation has to some extent seemed to embrace the term “Lean,” I wonder if an apology is in order for being disrespectful and failing to support and honor those who labored to create and evolve Toyota’s production system and overall management system.

This seems necessary because Western names associated with Lean long ago became more prominent than the Japanese names associated with TPS, thus erasing the people and culture. The names James Womack, Daniel Jones, Jeffrey Liker, Michael Rother, and Michael Ballé (all White) are better known globally than Kiichiro Toyota, Eiji Toyoda, Taiichi Ohno, Fujio Cho, and Kikuo Suzumura.

Cultural appropriation extends to Japanese words such as kaizen, jidoka, heijunka, poke-yoke, and many others that have deep meaning but whose Western understanding is extremely narrow. These have become loanwords, which is not necessarily a bad thing, but their meaning is greatly diminished when they enter the White lexicon of Lean.

For these and other reasons — association of Lean with layoffs, muddled understanding of Lean, executive disinterest in Lean — perhaps we should move on from Lean and circle back to the mindset and methods that matter most in relation to current and future business and human challenges: TPS and The Toyota Way.

Update: 27 August 2021.

Click here to read a lengthy rejoinder to my criticisms of the book title written by David Brunt, Chief Executive of The Lean Enterprise Academy.

My response to their rejoinder, posted on LinkedIn on 27 August, is as follows:

For being “much ado about nothing” this seems to be an extremely important thing – a lengthy 3336-word rejoinder to my few words of criticism. Despite the post being over the top, though historically interesting, I applaud your response! The post succeeds in defending against the title as cultural appropriation, but there remains a flaw in the argument regarding the word Lean: “To re-iterate, the term lean was used to describe what the researchers had observed at Toyota!” What researchers OBSERVED of TPS was much less than what could be understood. As with all that is generic, it is not exactly the same as the brand. Recall Fujio Cho’s words: “Our way of thinking is very difficult to copy or even to understand.” Researchers, not being TPS practitioners, surely suffer from this difficulty. I recall Chihiro Nakao’s words when I asked him a question about Lean. He said: “I don’t know anything about that.” What the book describes is the birth of TPS, (“Toyota System,” in the 2001 Japanese edition) not Lean. That is the fact, and so the title remains misleading because it suggests the generic is the same as the brand (i.e., “the standard”). As a teacher, my only interest it to get the facts right and challenge others to do so as well.

The LEA post that the title, The Birth of Lean, is correct, rests on fallacious arguments — the most obvious being a fallacy of composition: the inference that a partial understanding of TPS called “Lean” based on observation is the whole of TPS (1, 2). Other fallacious arguments include circular reasoning and appeal to motive (a type of ad hominem attack). Thus, the arguments defending the book title, as well as the book title itself, remains misleading to customers.

Yet there is a much larger problem for LEA (and LEI) to confront: the death of Lean. These are the words of our most famous Lean and TPS author and consummate insider: “As I suspect you all know lean seems to be waning in popularity as we move into the 21st century and digital is in, while non-digital is out…” (20 August 2021).

Back when the name “lean” came about, there was no customer demand (pull) for a generic description of TPS. It was thought that companies would not to do what Toyota did if it was called TPS. But as it turns out, most companies did not do anything close to TPS. They just picked the tools and methods that suited their interests. So creating a generic term for TPS turns out to have been unnecessary.