Recently, I have been re-reading some old books that I bought years ago to gain deeper insights into the relationship between economics and the prevalence and persistence of Fake Lean. By that I mean, the narrow use of Lean management by business leaders for the purpose of cost-cutting, in the furtherance of profit, especially in relation to its human impact; e.g. layoffs and other features that, inadvertently or not, harm employees, thus reflecting leaders’ noncompliance with the “Respect for People” principle. The books include:

- Unto This Last, John Ruskin, 1862

- A History of Political Economy, John Ingram, 1888

- The Modern Factory System, Richard Cook-Taylor, 1891

- The Theory of Business Enterprise, Thorstein Veblen, 1904

While economics is not the singular cause of Fake Lean, its presence exists on at least three bones of the fishbone diagram: people, methods, and measures. Economics, therefore, is a cause that surely contributes to the observed effect, Fake Lean. Economic thought operates in conjunction with business thought. Lean management operates within the realm of business. Therefore, economics is likely to play an important role in informing (or dis-informing) business leaders about Lean management. How and to what extent do they support or interfere with the creation of Real Lean, and prohibit an organization’s advancement towards Real Lean?

Certain core economic ideas developed centuries ago in England quickly became fixed in the minds of business leaders and remain intact to this day. The most interesting critiques of classical economics were made by those who were closer to it in time than we now are, and closer in time to the days when craft work and providing for the community were more dominant features of daily human life. These are rich and insightful readings about the past that inform the present. They offer to us an understanding of more than just the inner workings of conventional business mindsets and practices. They identify gaps in relation to how Lean management has been understood and practiced over the last 65 years, as well as how its predecessor, Scientific Management, was understood and practiced in the late 19th and early 20th century.

The critic’s detailed and careful analysis of classical economics, business, and management decision-making were typically grounded in facets of daily living, with reference to the virtuous characteristics of mankind created by God and as informed by religious writings and tradition. They were deeply skeptical of certain aspects of political economy, and questioned claims made as to its standing as a science, likening it instead to astrology, for example. It is noteworthy that pioneers of modern economic thought lacked scientific training and were “regarded with ill-disguised contempt” by actual scientists in part due to their blind allegiance to generalizations of human character.

The critics viewed science as something that helps people labor for that which supports or improves life. Political economy, with its acceptance of zero-sum outcomes, was seen as something that did the opposite and therefore resulted in destruction. The religious overtones of the critiques clearly indicate that such outcomes were new and unwelcome additions to human existence. Thus, ideas central to classical economics were seen as lacking in the moral dimensions integral to human ideals and human existence as bestowed by God.

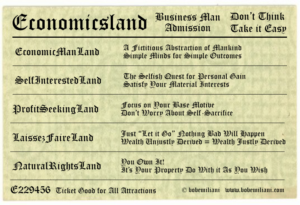

Some key concepts of political economics that these authors found to be very troubling include:

Some key concepts of political economics that these authors found to be very troubling include:

Economic man: This fictitious abstraction of mankind removes all other human variables to simplify investigation and analysis of economic phenomena. However, as God did not create such a man, none can actually exist, thereby negating economics both as a science and as a true guide for business owners.

Self-interest: The pursuit of self-interest and personal (material) gain were seen as secondary motives to one’s work. The prime motive for one’s work is service, self-sacrifice, to fellow human beings and the community – this is the sole characteristic that constitutes a “noble” or “great profession.” Self-sacrifice must be embedded in business, not “economic man,” whose quest for gain is happily pursued in zero-sum fashion. “Self-interest” precludes business from consideration as one of the “great professions.”

Profit-seeking: This was seen as a base motive, one that grossly conflicted with the virtue of self-sacrifice. “Money-gain” was not viewed as true gain. The number of happy human beings was seen as the measure of richness. Profit-seeking brought wealth to owners and poverty to workers, and made it difficult for workers to feel affiliated with an organization knowing that owners may cast them aside at any moment and thereby fracturing human relations.

Laissez-faire: The concept of “let it go,” self-regulation, was seen by critics as “the devil’s philosophy,” an excuse for leaders to avoid their responsibilities to lead, to avoid work, and to avoid providing for the community to sustain life. Relatedly, there was strong moral disagreement with the idea that wealth unjustly derived is economically equivalent to wealth justly derived, the latter resulting in inequalities in wealth that disadvantaged workers and community interests.

Natural rights: Human being’s intrinsic or natural rights to life, liberty, and property, where ownership is given by one’s own work or by trade or by inheritance. Particularly, freedom by an owner to do as he wishes with his property, the business, and all material and human resources contained within it – to the detriment of the community.

In different ways and to varying degrees, these classical economic concepts were seen anti-human, un-human, or working against human interests given by God; e.g. of cooperation (teamwork), community, work, livelihood, and life. Respect and service, self-sacrifice (unselfishness), are intertwined. Remove self-sacrifice, and one removes respect. Thus, the foundation is laid for trickery and deceit in pursuit of one’s own interests, which leads straight to destruction. According to Cooke-Taylor, “The motive of self-interest leads men to wrong-doing more often than to right-doing, and should therefore be replaced by the motive of public interest.”

The critics decried the acceptance of these five economic ideas with no critical thought, particularly those that exempted humanity from money-making. They viewed elements of classical economics as deeply disrespectful of people. It corrupts and compromises the virtuous gifts that God gave to humans, and reduces God’s influence and lowers His rank. People were seen as the true source of wealth, and service as the true purpose of one’s work.

Yet, the economic concepts cited above were quickly adopted by businessmen, most likely because they confirmed their biases. Unable to objectively judge the value of the human or his work, businessmen were easily able to objectively judge all matters in relation to “pecuniary interests.” These economic ideas soon became a “habit of mind” immune to criticism or re-consideration. They became entrenched for nearly two centuries and could not be appealed no matter how cogent the argument was.

Work, enmeshed with economics, must develop one’s humanity, not remove it. The combination of classical economic concepts, profit-seeking, and complex machinery were seen as a detriment to the further development of workers’ humanity, impairing their ability to absorb the world around them and bring forth their imagination and creativity into their work, and was, therefore, soul-destroying. Borrowing from Veblen, one can sum up by saying: “[Economics], their master, is no respecter of persons and knows neither morality nor dignity nor prescriptive rights, divine or human.”

• • • • • • • •

So how does this relate to Real Lean management?

The common thread that runs through the five economic concepts is disrespect for people. They give explicit permission to owners and managers (at all levels) to disrespect people in the furtherance of business ends. They either greatly discount or completely discard “Respect for People,” both in its casual definition and especially its many meanings within the context of Lean management. Classical economics, therefore, clearly introduces a defect into businessmen’s thinking in relation to Lean management, disrespect for people, which is deeply consequential in terms of its human impact. Discarding the “Respect for People” principle allows leaders to avoid work in that same way that laissez-faire was seen as an excuse for leaders to avoid work.

Lean management is meant to achieve many things. Among them is the restoration of economic and social fairness to employees, not the opposite as these ideas in classical economics compel business leaders to do. If business owner’s thinking is suffused with these key economic concepts, then it is logical to conclude that “Respect for People” is of little or no interest. This renders itself as a rigid structural problem in the advancement of Real Lean management. The practical consequence is that people are treated as costs that owners can dispose of as dictated by necessity or whim, to assure continuity of profit. Because this is the prevailing “habit of mind” among business leaders, the prevailing outcome will be Fake Lean.

Is there a remedy? If so, what could it be? A way forward lies in re-thinking how business leaders are introduced to and trained in Lean management. There are likely other ways forward that will need to be used in combination, but let me put this one forward for now. Perhaps you can think of others.

One of the things we learn from participating in kaizen is that we have much to unlearn about our knowledge of processes and people. As we dive deeper into Lean management, we discover many more things to unlearn and many completely new things to learn. Often, we learn things later that we wished we had learned closer to the beginning of our Lean experience, as this would have helped us move forward faster.

For many years, and to this day, Lean leadership training begins with Lean tools, leadership behaviors, or both. These should no longer come first; they should come later – perhaps much later. As I have previously pointed out on numerous occasions, Lean leadership training must begin with leaders’ beliefs, and in this context, their beliefs about economics. If a leader’s understanding of economics is such that it excludes the “Respect for People” principle, then it is pointless to train them in Lean tools or how to improve their behaviors.

For senior business leaders, Lean training must have a different starting point. As one would fight fire with fire, one must fight pecuniary interests with pecuniary interests. Specifically, the ideas embedded in classical economics that create a “habit of mind” that discounts humanity and results in Fake Lean. Business leaders must be shown, likely in clever and resounding ways, how certain ideas in classical economics conflict with both of the bedrock principles of Lean management, “Continuous Improvement” and “Respect for People,” as the two are deeply interwoven. And, that in order to achieve the wide-ranging benefits of Lean management over the long-term, the economic mindset must change as well as the management methods.

Obviously, this is not a silver-bullet solution. None exist. However, it is clear the focus of and methods for training business leaders cannot remain the same. What business leaders learn about economics in college or graduate school is probably out of our control. Everything about Lean is learned on-the-job and in corporate training. And so it must be when it comes to Lean management and economics.

Finally, we must recognize that workers are tired of Fake Lean, and its continued presence will almost surely lead to the decline of the Lean management and the demise of the Lean movement. But, most importantly, we must do all we can to protect workers from Fake Lean, now and into the future. It has never been acceptable to have a laissez-faire attitude towards Lean failure (a condition that is likely due to the pursuit of self-interest and profit-seeking). We must understand the causes of Lean failures using formal failure analysis methods and take what we learn to improve life. Remember, the prime motive for one’s work is service, self-sacrifice, to fellow human beings and the community.