Lean world has long thought it can move forward quickly and effectively by knowing only its side of the case. That has been a big mistake, and it accounts for a wide range of difficulties. Additionally, ignoring the the other side’s view communicates an obvious lack of respect.

But when we turn to subjects infinitely more complicated, to morals, religion, politics, social relations, and the business of life, three-fourths of the arguments for every disputed opinion consist in dispelling the appearances which favour some opinion different from it. The greatest orator, save one, of antiquity, has left it on record that he [Cicero] always studied his adversary’s case with as great, if not with still greater, intensity than even his own…

He who knows only his own side of the case, knows little of that. His reasons may be good, and no one may have been able to refute them. But if he is equally unable to refute the reasons on the opposite side; if he does not so much as know what they are, he has no ground for preferring either opinion. The rational position for him would be suspension of judgment, and unless he contents himself with that, he is either led by authority, or adopts, like the generality of the world, the side to which he feels most inclination.

— John Stuart Mill (1806-1873), British Political Economist, On Liberty (1859, p. 66-67)

The argument FOR Lean management is forever weak when you have no knowledge of the argument AGAINST Lean. If you listen to only one side of an argument, you develop prejudices against any other argument and are thus much less well informed about the overall subject — and less able to make change. Consequently, you should understand the arguments that you disagree with. That applies across a range of problems related to the advancement of Lean management.

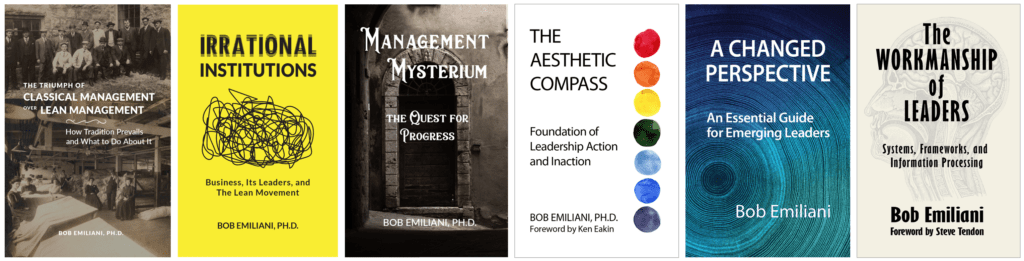

These six books attest to my record of studying our “adversary’s case” with greater intensity than my many books favoring Lean management.