The modern era of progressive management, beginning after World War II and pioneered by Toyota Motor Corporation, followed by the arrival of Lean management in the late 1980s, has led to the production of many books describing the principles, methods, and tools. The number of books produced between 1988 and 2019 exceeds that produced in the earlier era of progressive management, Scientific Management (ca. 1910-1940), by a wide margin. I know this because at one time I had collected some 95% of all Scientific Management books published, which totaled about 70 titles.

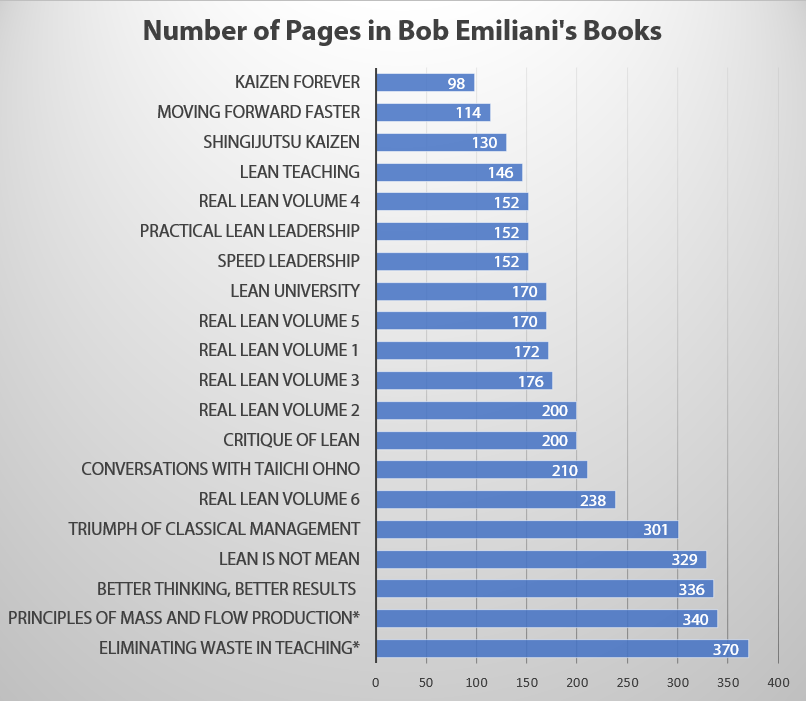

Recently I became curious to how many books about Toyota and Lean had been written in English. To make my job a bit easier, I looked for authors who wrote two or more books (my apologies to any authors that I may have missed). I decided to plot the data according to Mark Graban’s recent book, Measures of Success: React Less, Lead Better, Improve More, in part because the number of books written can be seen as one (of many) measures of success. Other measures of success could include the number of books sold, income earned from royalties, influence among managers or non-managers, number of organizational transformations, etc. The image on the right shows the results.

The top chart shows authors, listed alphabetically, who have been engaged in the process of documenting modern progressive management as measured by the number of books published. The green line shows the average number of books written among the 26 authors (n = 160). The middle chart shows the upper and lower control limits (red lines). The bottom chart shows the moving range. The bottom chart does not provide any useful information, but it was fun to create. Overall, the results are interesting both numerically and visually.

To my knowledge, book authorship data has never been presented in this way before. Is it useful? Well, it can help people understand who are the principal authors of two or more English language books in a very important field –- management — which has profound effects on people’s lives and livelihoods, for better or worse. By ” better or worse” I mean whether Lean management is adopted or not, organizationally or individually, including troubles that may arise from its adoption.

So what did I learn from making these charts?

- There are more authors of two or more books than I thought there were.

- Authors are while-male dominated (76 percent), 11 percent female, 11 percent Asian, and 4% Hispanic/Latino (Emiliani).

- The average output of books among the authors listed is 6.15 — higher than I would have guessed.

- There are several books that I was unaware of and which I now want to read.

- The early authors, e.g. Ohno, Womack and Jones, Rother, etc., have produced the fewest books but their work has been the most influential.

- As with Scientific Management 100 years ago, people worked to document the then-modern management practice. Their output of books, singly and in total, can be seen more as a measure of the popularity of the movement (i.e. a measure of success) than of its success in transforming organizations (another measure of success). The same appears to be true today for Lean management — a popular movement, but few transformed organizations. That outcome suggests we did not learn from the past; that our focus on producing lots of books, while well-meaning, was misdirected. Therein lies opportunity for improvement.

The middle chart reveals a “signal” for the metric “number of books.” The signal is the data point above the upper control limit, below which lies my name. I have been the author or co-author of 20 books (the 20th book will be published next month). Assume this were a data for an assembly operation (which is what writing is). There are 26 “operators” whose output ranges from two to 20. Looking at the data through the lens of industrial engineering, one would ask “Why is one operator’s output so much higher than the others? What’s different about their process? Let’s learn more.”

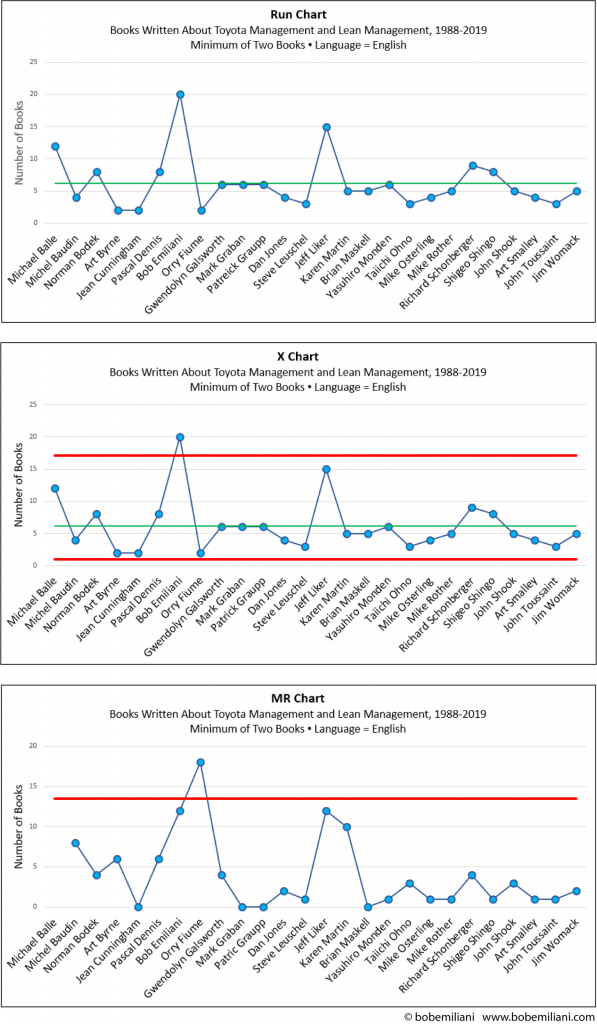

Book writing and getting a manuscript published is a daunting task for most people, especially if writing does not come easily. It is usually a difficult and very time-consuming process. And the money (royalties) are not great — unless the book sells hundreds of thousands of copies. So the payback is often poor. Book writing is usually treated a big project. But it is not that for me. First of all, I have 40 years of professional writing experience, and so writing comes easily to me. Secondly, I have applied Lean principles and practices to book writing and publishing, some details of which are described here. Simply stated, I do many small book projects quickly rather than a few large book projects slowly. Over a 16-year period, I have produced a steady flow of books averaging of 1.25 books per year. And writing, of course, is not my full-time job. It is one of my leisure activities.

The image at right tells the story in terms of page count for my books. Knowing that the audience is mostly businesspeople who do not like to read thick books, most of my books are less than 200 pages. They are slim volumes that are perfect for reading on an airplane. If you exclude the last two books (noted by asterisks), which are republications of other people’s work (to which I contributed 50 to 80 pages of commentary and analysis to each), the average page count for 18 of my books is 191 pages. By the way, the total number of pages I have written is 3577 (including two the books with an asterisk).

Why have I written so many books? It’s simple. I’m curious to learn new things, I enjoy writing, and I feel a duty (as a professor) to share what I have learned with others in the most affordable way — which is paperback books. In addition, Toyota and Lean are wonderfully rich areas for practice, study, and comparative analysis of leadership and management (as was Scientific Management before them). I long ago developed processes consistent with Lean thinking that have removed much of the burden typically associated with book writing and publishing.

And finally, I decided long ago to put everything I know in writing. This is not what a consultant does. Instead, it is consistent with my role as a university professor, in which we happily make our work available to people at low cost or no cost. Books and other writings are the fastest and most economical way to convey information to people interested in the subjects that I have written about. It also provides a lengthy record for those who may one day conduct research on my work without the burden of having to go through boxes and boxes of personal archives — of which there are none (well, there is an exception, my one box of reference books and handwritten notes for the book The Triumph of Classical Management Over Lean Management). Aside from that single exception, I throw out all my notes after a book is written.