In the blog post “Lean Zombies,” I said:

When one looks at all the great management thinkers over the last 100 years — from Taylor, the Gilbreths, to Follett, Mayo, Deming, Drucker, Argyris, Kanter, Senge, Schein, etc. — they have all had senior leaders’ attention (and lucrative consulting work) at one point or another. But whatever they may have taught executives has proven to be largely non-transferable from one generation of leaders to the next. All of this great thinking has proven to be largely ephemeral; curiosities that do not have staying-power. Most top business leaders lead the same way that leaders before them led, for generations.

People who are dedicated to improving the understanding and practice of management to improve company performance and the plight of disaffected employees face this problem whether they realize it or not. The troubling aspect is the lack of curiosity about why this happens (cause-and-effect) and the use of a methodology that will almost certainly lead to a repetition of history whose outcomes were less than favorable.

The methodology being, come up with a new system, concept, process, technique, or tool that can or will improve management practice (e.g., Lean management, brain science), and then go to market — top business leaders being the market — without learning the experiences and outcomes of others who have previously tried to do the same thing.

Each time, the creator or inventor of the new product goes to market with high hopes. If they are fortunate, sooner or later they find a lot of interest in their product and the creator will gain much sought-after credibility and great confidence.

But eventually, the creator or inventor of the new product learns what all others before them learned: Only a few top leaders were willing to put the product into practice in the way that can deliver the advertised result. All other leaders who found the product interesting and who helped generate a lot of hype did not change the way they managed. Most leaders preferred the status quo, classical management. What is old is seen as having greater intrinsic value and is thus worth preserving. Their shared view is that what is new is interesting, but likely bad because it is new. So, it is best to avoid new management innovations. Furthermore, hewing to tradition is an act of solidarity among high status leaders and reduces both social and existential risk.

This leads nearly all the management innovators to the same conclusion: “We can only work with those [who are] interested. Period.” Or, “I’ll settle for helping those who have an interest.” Or, “If the CEO is not interested, you must walk away.” These rationalizations seem both logical and practical, and given that there are over 300 million businesses worldwide, statistically there will be some business leaders who will be interested in the new product. The strategy of working with those who are interested produces the requisite income for the creator and satisfies some leader’s needs.

Yet, this methodology has a glaring weakness: There is no learning from the mistakes of others and no interest to learn why innovations in management practice are largely ephemeral. Creators’ enthusiasm for their new product, going to market, the allure of sales, positive feedback, etc., are all forward-looking and thus subvert consideration of what could go wrong. But the problem always remains: Why are most top business leaders uninterested in improving the practice of management?

People have little awareness, understanding, or appreciation for how leaders’ status relates to the problem of improving the practice of management. People with high status are the arbiters of what is good or bad, beautiful or ugly, right or wrong, and useful or useless. They are the tastemakers and influencers. People lower in status consent and readily follow their leaders, even if it does not serve their interests (e.g., low-status employees enthusiastically implement the productivity improvement innovation that costs them or others their jobs). Of course, there are always a minority of low-status individuals, within or external to the company, who will challenge the canons and conventions established by those highest in status. Their efforts are largely ignored by both the high status influencers and the low status influenced.

Business leaders occupy a unique position in society. They sit atop both the company hierarchy and, consequently, the larger social hierarchy. Their personal and corporate economic power and connections to politicians means they can do pretty much whatever they want. Consequently, their personal and business success is independent of any new system, concept, process, technique, or tool that can or will improve management. Interest in any such management innovation is totally discretionary and thus instantly reversible.

Any management innovation is seen by most top business leaders as provisional; it is time-limited in its utility and subject to modification or removal as times or needs dictate. Management innovations, like employees, serve at the pleasure of the leader, in whatever form they deem most useful to them personally or for the business. That is their right and privilege. And when the top leader leaves the job, the next leader takes over and determines anew what is good or bad, beautiful or ugly, right or wrong, and useful or useless. Whatever the prior leader did could be left alone, strengthened, or undone, but likely undone if it is seen to have violated the norms of traditional classical management practice. Any new management innovation will serve at the pleasure of the new leader, and the cycle continues.

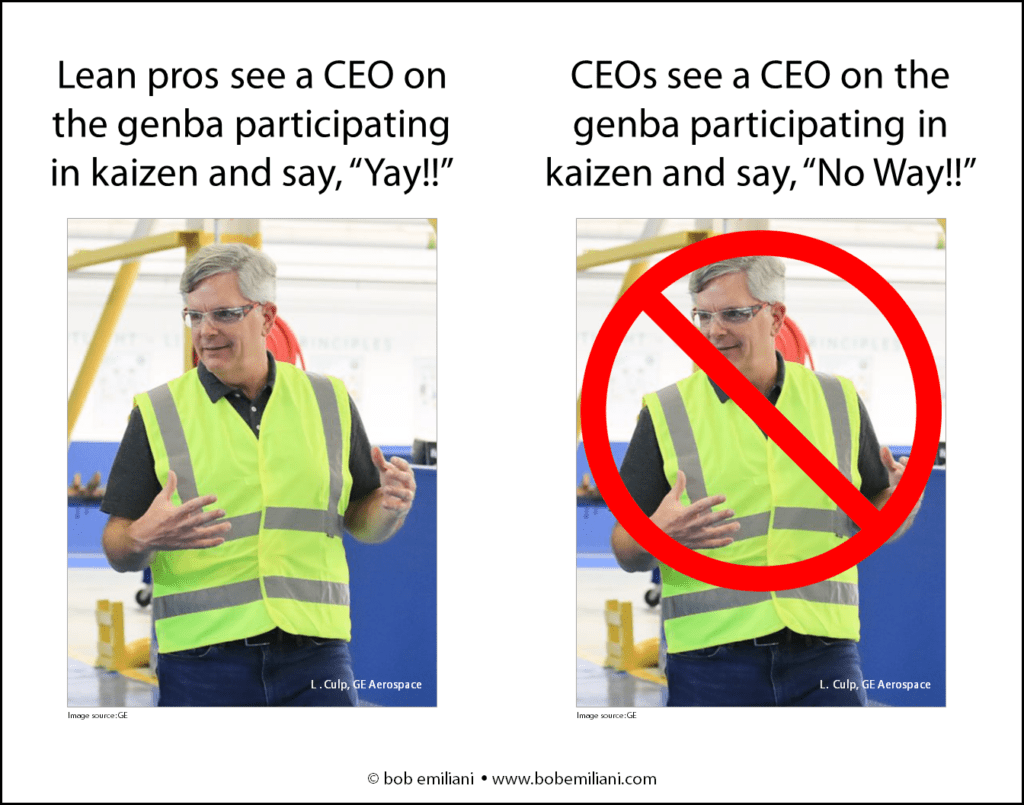

In almost all cases, management innovations over the last 75 years have come from people who are lower in status than business leaders. From the perspective of a high status business leader, the management innovation is theirs to use, shape, destroy, or ignore as the see fit. To use it as prescribed by the lower-status innovator is a low-status act and must be avoided (negative cachet). If a management innovation happens to come from one of their high-status peers, then they are likely to practice it as prescribed, keep using it, and pass it along to the next generation of top leaders.

In simple terms, classical management has been judged to be good and right, lawful and legitimate, tested by many top leaders over long periods of time. It is tried and true, durable, and a revered anchor to the past and past success. Therefore, all else must be wrong, in part or whole, even if it is better and more effective. And so, the top leader will exercise their right to amend or ignore management innovations as they desire. This gives the appearance of management innovations as being fads. But what is really going on is a rejection of progress in management thinking and practice by high status leaders, and the reclaiming and revalorization of classical management owing to its historical value which certifies a claim of authenticity.

The people who create management innovations have yet to figure out how to position their innovation as a marker of high status, given that newness certifies a claim of inauthenticity. This is not easy to do because progressive management represents a major reassessment and realignment of traditions and beloved status criteria, something that most top leaders have little interest in doing. Yet, there could someday be significant events that force a change in management thinking and practice. But will it be sustained, and by what means?

Does all of this mean that people should not try to improve the understanding and practice of management? No, they should. But, after more than 100 years of efforts to improve the understanding and practice of management, one must go into this work with eyes wide open and have an interest in learning from the difficulties and mistakes of others that preceded them.

The biggest mistake management innovators can make is to lack the curiosity to understand their high status customer. Yet, for most management innovators today, the master plan is to repeat the mistakes and frustrations of the past rather than learn from them. If a management innovator wants things to go according to plan, then they must learn the causes of why things do not go according to plan by studying the difficulties and failures of others before them.

In the six books shown below, I have thoroughly deconstructed how status regulates progress and explain the mechanics that allow classical management to retain its dominance. I cannot force you to read these books, and I cannot assure you that reading them will give you all the answers that you desire, but I can guarantee that you will gain a solid understanding of what you are up against.

My hope is that the post helps people recognize, or more clearly recognize, the uniqueness of top leaders in relation to their interest to improve management practice, employee engagement, and business performance. Such knowledge can help management innovators find ways to have longer-term impact.

SIDEBAR 1: The importance of status and status signaling in leadership culture should help you realize that the century-old focus on changing top leaders’ behaviors is deeply misplaced. Those high in status have very low tolerance for doing what others low in status want them to do, even if leaders show interest in the management innovation.

SIDEBAR 2: Status and status signaling explain why high status leaders tend to ignore the concerns and advice of low status people such as scientists, engineers, workers, etc. It is sufficiently often to the detriment of the high status leaders such that they should err on the side of caution and listen to those who are lower in status. But doing so lies in conflict with the Institution of Leadership and System of Profound Privilege. Therefore, it incurs social risk.

SIDEBAR 3: Even if one was to create a management innovation that successfully replaced classical management quickly and on a large scale, high status leader’s nostalgia for the past (retro) assures that classical management will return.

SIDEBAR 4: It is notable that those at the top of the hierarchy have a strong, often reflexive dislike for government regulations, a status-derived form of regulation (given that government stands above individuals and society), while at the same time they cherish their ability to regulate progress over individuals, business, and society by virtue of their status.