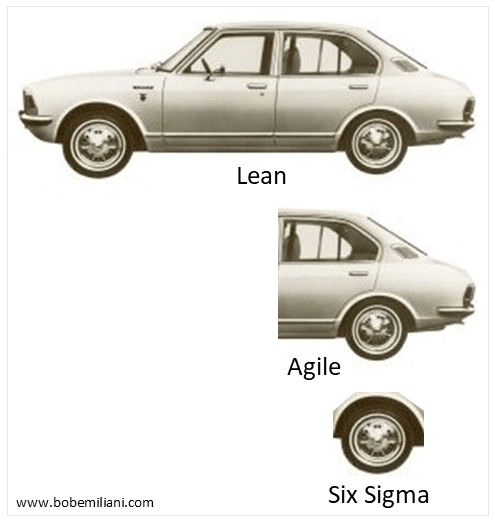

One of the ongoing arguments that people have is that Lean is a system, while other things that have borrowed from Lean or attached themselves to Lean are somehow the same as Lean (and thus, a system). The image at right is an imperfect conceptual model featuring a 1971 Toyota Corolla that illustrates the point, in a thought-provoking way, that not everything derived from TPS or Lean is a system.

One of the ongoing arguments that people have is that Lean is a system, while other things that have borrowed from Lean or attached themselves to Lean are somehow the same as Lean (and thus, a system). The image at right is an imperfect conceptual model featuring a 1971 Toyota Corolla that illustrates the point, in a thought-provoking way, that not everything derived from TPS or Lean is a system.

Using “system design hierarchy” terminology, Lean is a complete system, Agile is a distinct sub-system (missing/different parts), Six Sigma is a component (tool). The relation of both Agile and Six Sigma to Lean is borrowed and confused. Importantly, in viewing this image, it is important to recognize that Lean ≠ TPS, meaning that Lean is not the same as TPS, and Six Sigma ∉ {TPS}, meaning that six sigma is not a component of Toyota’s Production System.

The image speaks to widespread confusion that exists surrounding TPS, Lean, Agile, Lean Six Sigma, Six Sigma, and so on. The point of the image is incomparability; as in, not the same thing. A component (tool) or subsystem is not the same as a system. Many people protest and say: “The ultimate outcome expected from all these methods is continuous improvement.” But is the actual result continuous improvement? Certainly not as often as one would like — perhaps even rarely. What we have mostly is results that fall well below expectations. The common outcome ranges from failed Lean transformation processes to small improvements that take a very long time to achieve and which have little business impact.

It is remarkable to see how over time, Lean, Agile, Lean Six Sigma, and Six Sigma, have evolved from somewhat precisely defined things to whatever people think it is or what they want it to be. Seen from a Darwinian perspective, the principles, methods, and tools of TPS in the hands of others result in mutations and adaptations that may or may not be useful, but which nonetheless prosper because they are the fittest in the business environment. This re-packaging can serve different ends: creation of a new product to sell, adaptation to a particular company’s needs, mutation to accommodate leaders who are resistant to change, inadvertent mutation based on misunderstandings, etc. The process of Darwinian evolution of Lean is now far along, and it will be interesting to see what survives either whole — barring unforeseen circumstances — or, more likely, in part.

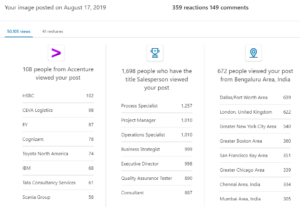

And it seems widespread that people do not know what success — Lean transformation — looks like. This, despite countless benchmarking visits to Toyota and dozens of other companies over the years that have experienced favorable results, and dozens of books describing successful transformation (both method and results). The Toyota Corolla image generates some perspective and contains a certain element of truth that people can relate to. The image at right shows the metrics for the Toyota Corolla image when I posted it on LinkedIn on 17 August 2019. It had tens of thousands of views and generated lots of discussion online.

Because of the mutations, adaptations, and resulting confusion, there is a sensible call to return to the fundamentals of TPS to achieve the needed business results which include culture change, material and information flow, and related attributes characteristic of Lean transformation. This, too, is controversial because many people view it as a return to analog era process improvement work when we should move on to digital era process improvement work. The reality is, both are needed.

Yet a return to fundamentals of TPS to achieve needed business results is unlikely to happen. Over time, people have lost faith in Lean’s promise (the system) to deliver outstanding results to business and other organizations. And people (especially executives) have tired of hearing about Toyota and how they do things. The mindset has shifted to using whatever tool works best to solve the problem at hand, from whatever source. In doing so, the status quo is maintained in terms of enforcing individual accountability (versus improving the system). In addition, it will result in the introduction of methods and tools that conflict with TPS and Lean principles and practices, likely creating even more confusion.

Furthermore, I am struck by the fact that it takes a lot of practice using a method or tool to understand it well and to get good results from it. Casual application of problem-solving methods and tools usually produces poor results. Take the “5Whys” root cause analysis method. I have witnessed many corporate Lean “experts” who cannot produce a logical 5Whys analysis. Neither can most of my graduate students who are working professionals and claim they know how to do a 5Whys root cause analysis. Another example is 5S. People don’t understand its origin or its proper application relative to Just-in-Time.

So, predictably, classical management is once again prevailing, just as it did 100 years ago under the threat of Scientific Management. The only change to classical management is the addition of new methods and tools borrowed from TPS and elsewhere to solve whatever problem one encounters. Employees will have to contend with an ever-expanding corporate toolbox that they are expected to demonstrate compliance with. It is possible that the methods and tools most used are the ones that best give the appearance of having solved a problem?