In my new book, The Triumph of Classical Management Over Lean, I identified 17 bedrock assumptions that have guided the promotion and marketing of Lean to large corporations. However, there are many more assumptions than that. The assumption that I would like to focus on here is the nature of the joint-stock corporation, it’s understanding of work, and its relationship with employees.

In my new book, The Triumph of Classical Management Over Lean, I identified 17 bedrock assumptions that have guided the promotion and marketing of Lean to large corporations. However, there are many more assumptions than that. The assumption that I would like to focus on here is the nature of the joint-stock corporation, it’s understanding of work, and its relationship with employees.

When the term “lean production” was first introduced to the public in 1988, it presumed that the corporation, as an industrial unit, had productivity and workmanship (quality) as its primary concerns. This viewpoint was based on the prevailing political perspective associated with international competitiveness in the automotive industry, which, in turn, influenced the perspectives of the academic researchers who studied Toyota. This perspective was assumed to accurately represent the corporate executive’s perspective. But what if it did not? What if corporate executives confirmed the biases of politicians and Toyota researchers?

The concept of the corporation was created in the mid-1800s for individuals (investors) to pursue profitable lines of business activity with the personal protections afforded by limited liability. We think of the corporation as an industrial unit, but it is actually a pecuniary (financial) unit — nothing more than a means to make money, irrespective of the goods or services produced. Generally, top executives charged with fiduciary responsibility have only passing interest in the items sold. The only time they care about the product or service is when sales slow down.

As a derivative of Toyota’s management system, Lean was deeply influenced by the thinking of Toyota leaders – a succession of leaders who placed great emphasis on productivity and workmanship (i.e. quality through craftsmanship). Toyota leaders also possessed a different concept of the corporation – one that must survive for the long-term (hundreds of years) rather than something to be sold, merged, or liquidated at the whim of investors. Toyota leaders’ view of the corporation and its productive activities (“monozukuri”) is unique, rather than common, among corporate leaders.

Toyota’s leaders also believe that profits are the result of: 1) making people who 2) make good things that 3) satisfy customers. Corporate executives see things differently than Toyota executives. They see that corporate profits come from selling things, whether they are made good or not, by whomever, and whether or not they satisfy customers. While profits can be increased through productivity (process) improvement, productivity as a pursuit is secondary to the pursuit of profits. Production is incidental to money-making, and thus it garners little interest among corporate executives.

These clear differences in perspective suggest a massive misreading of the then (and now) current state of the joint-stock corporation and the interests that drive executive thinking and decision-making. It means that the basis for promoting and marketing Lean over the last 30 years has been far off-target. And it has been largely stagnant as well, with only a few adjustments in 30 years.

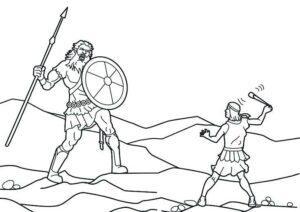

The general population of corporate executives can be classified as P-Type executives (or S-Type), while Toyota executives are H-Type. These types of executives are vastly different, something akin to salt and pepper or fire and water. Promoting and marketing Lean to P-Type executives as if they are (or want to be) H-Type executives is foolish. Common marketing practice suggests that marketing to P-Type executives should be based on their individual interests and needs.

However, if you do that, Lean is reduced to various tools used by workers to make only marginal improvements in cost, productivity, quality, and lead-times. This is what we have witnessed time and time again. P-Type corporate executives took the H-Type executive Lean marketing message and sharpened it to fit their individual interests and needs. They successfully remarketed Lean, much to the consternation of everyone promoting the H-Type executive marketing message.

The people-centric nature of Toyota’s management system, and of Lean, are not even partially realized. That is because the joint-stock corporation is impersonal, partly the result of ownership that is both distributed and passive. It is impersonal by design. Profits matter most, and these are had by salesmanship and gamesmanship (CEO Wealth Creation Playbook). And we must accept that salesmanship and gamesmanship are much easier for P-Type executives to execute than Lean, which is alien and thus far more difficult to understand and execute. In addition, any gains must come at someone else’s expense. The joint-stock corporation is disrespectful of people by design.

The P-Type executives’ appreciation of workers and craftsmanship resides outside of the corporation. Wealthy executives will marvel over the material, design, labor, and craftsmanship contained in their $85,000 custom motorcycle, their $150,000 custom watch, or their $40,000 custom rifle. Yet they are indifferent, if not hostile, to the craftsmanship of the employees who make the product or service that the company sells to its customers. This illustrates the difference in perspective of the P-Type executive within and external to the confines of the joint-stock corporation. The worker who supplies luxury goods is celebrated as a true craftsman, while the employee who does the work is scorned as a cost and a burden to be eliminated.

Obviously, neither Toyota’s management system nor Lean are designed to defeat such a system. They will win here and there (a few lucky sling shots), but, for now, have zero chance of winning everywhere. Art Byrne, the retired CEO of The Wiremold Company, is fond of saying “Lean provides an unfair competitive advantage.” But, as this post and The Triumph of Classical Management Over Lean clearly reveal, that is not actually the case. Unfair competitive advantage goes to the corporation, it’s leaders, and to classical management. And their unfair competitive advantage has been greatly strengthened in the last 20 years.

One of the big problems the Lean community faces is that it keeps doing things the same way. That is odd for a community devoted to continuous improvement via experimentation. Always keep in mind the wise words of Henry Gantt: “The usual way of doing a thing is always the wrong way.” Given these facts, Lean’s promoters must think anew and rapidly experiment with other ways of advancing Lean in large corporations. They cannot keep doing the same things and expect a different result.

Alternatively, it might be more wise to focus efforts to promote Lean on startups, B (Benefit) corporations, SMEs, and non-profit organizations.