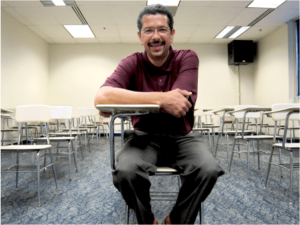

My full-time job since 1999 has been as a professor of Lean management at a university, where I teach both graduate and undergraduate courses. My areas of specialization are: Lean leadership, Lean management, management history, management decision failure analysis, and supply chain management. One of the job functions of professors is to share (and critique) knowledge that has been produced by other academics (and practitioners), as well as share one’s own research — their problem-solving work. And so we continuously educate ourselves and other people through the discover and distribution of knowledge, and we so so with an egalitarian spirit and with wholesome intentions.

My full-time job since 1999 has been as a professor of Lean management at a university, where I teach both graduate and undergraduate courses. My areas of specialization are: Lean leadership, Lean management, management history, management decision failure analysis, and supply chain management. One of the job functions of professors is to share (and critique) knowledge that has been produced by other academics (and practitioners), as well as share one’s own research — their problem-solving work. And so we continuously educate ourselves and other people through the discover and distribution of knowledge, and we so so with an egalitarian spirit and with wholesome intentions.

Our purpose as teachers and as researchers, is, at the highest level, to help people — not just students, but any consumer of information. We teach people things, as best we can, under the various limitations we face, that they will hopefully find useful in their life and in their work. And we try to do this in the most accurate way possible, which includes examining minute details to help assure our understanding of facts (the truth), which we convey to others. Good professors share facts when teaching in the university, not opinions.

I am often asked, “Why do you write so much.” In large part, it is because it the job of professors to think, problem-solve, and explore the boundaries of knowledge in their respective fields. We conduct research, generate new knowledge, and share new knowledge, principally by writing academic research papers and books. Professors also share information by other means such as engaging the public outside of the university. This includes, public speaking, interviews, webinars, blogs, and so on — and in these settings, professors share both facts and opinions.

A professor engaged in teaching and researching Lean, especially one who has hands-on experience with Lean in both industry and academia, and who trains executives in Lean leadership, is rare among the vast numbers of Lean consultants, trainers, writers, and speakers. Because of my unique background, and the job of professor that requires one to think, I examine things in detail and then write about them. Long ago, I discovered that there can be a great distaste in some quarters of the Lean community for closely examining the details. Simply put, they do not like someone to challenge Lean movement leaders or what has become “settled” Lean knowledge or practice. This is an odd way for Lean thinkers to think. This is an odd way for skilled problem-solvers to react to the work of other problem-solvers. The presumption of competence quickly and effortlessly awarded to others must be endlessly, but never quite, earned by those who do not conform to the standards and canons of Lean culture.

Because my problem-solving (research) work looks at things that others prefer not to look at or wish to be left alone, I have been confronted by people, whom you surely know, with bizarre claims. For example, one person said to me (paraphrasing), “Why do you think you are the only one who understand Lean?” That is such an odd thing to say coming from someone who, like myself, knows full well that it is impossible to know Lean — we’re never done learning. Day 1 of kaizen training makes that completely apparent. My extensive writing reflects a great interest (a.k.a. “curiosity”) in wanting to know more about Lean, not satisfaction that I know or understand Lean. I thought that was obvious, but apparently not. And, remarkably, some of the noisiest advocates of “Respect for People” in public put on a much different face in private, one of disrespect in the forms of disparagement, bullying, intimidation, passive-aggressiveness, and ad hominem attacks. For example: “You are a nothing, a nobody… You are worthless.”

Hansei is an important part of the practice of TPS and Lean. It means to reflect on one’s errors and commit to making improvements. To that end, here are ten areas for all members of the Lean community, and particularly its leaders, to reflect on:

- Embrace greater diversity of thought and inclusion

- Accept diverse roles and interests (vs. those who merely “toe the line”)

- Practice “Respect for People” in private as well as in public

- Abandon complaining about what executives should or should not do (as this is not problem-solving)

- Become more interested in why people struggle with Lean and how Lean transformation processes fail (this is problem-solving)

- Do not glorify improvements that have no business or human impact

- Stop relying on fads (“flavor of the month” tools) to fuel interest in Lean (and instead focus on items, 5, 9, and 10)

- Stop promoting Toyota mindset and methods as the only measure of worth of improvement ideas or practices

- Understand the long historical arc of progressive management and the details of why it has failed to displace conventional management

- Teach people interested in Lean all three things that they need to know: How to succeed, the barriers they will encounter, and the common failure modes (vs. just one: how to succeed)

Overall, the opportunity for improvement in the advancement of Lean is intellectual honesty — “an applied method of problem solving, characterized by an unbiased, honest attitude, which can be demonstrated in a number of different ways: One’s personal faith does not interfere with the pursuit of truth; relevant facts and information are not purposefully omitted even when such things may contradict one’s hypothesis; facts are presented in an unbiased manner, and not twisted to give misleading impressions or to support one view over another; references, or earlier work, are acknowledged where possible, and plagiarism is avoided… Intentionally committed fallacies in debates and reasoning are called ‘intellectual dishonesty’.” In other words, the avoidance of deception.