I will venture to guess that the people who love Lean management have an affinity for helping to make processes run smoother, with less struggle, and with fewer problems, with the overall goal being productivity improvement at the genba. That is an important goal given that most businesses face competition in the marketplace and thus have the need to improve productivity in all business processes.

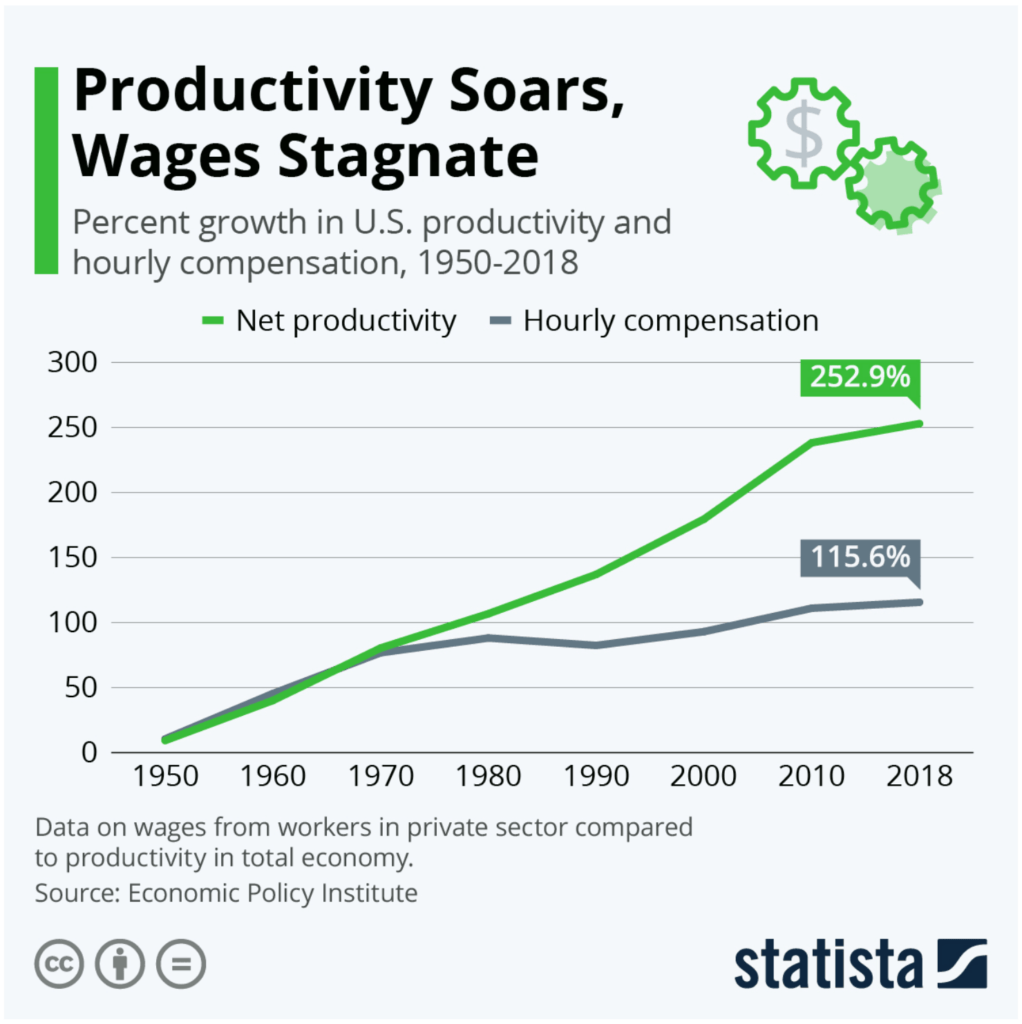

One thing that I have struggled with for many years is promoting the thinking, system, methods, and tools whose results lead to productivity improvement, the gains of which, since the 1980s, have barely been shared with those who do the work. The wages of the people on the genba, doing the actual productive work, and who are constantly challenged to improve productivity, have received little in the way of higher wages and benefits as the chart below shows.

The chart begs the question: How can Lean pros be so supportive and respectful of genba workers, “the experts,” yet allow them to languish economically for decades? Why no broad-based advocacy for fairness? An obvious defect in Lean is no provision, no demand, to share the economic gains from productivity with workers.

Of course, neither Lean nor Lean pros are the sole cause of this problem. The influential neoliberal economic doctrine (now falling out of favor after 50 years) of Milton Friedman (read his highly influential 1970 New York Times essay here) and the even more influential 1976 work of Michael Jensen and William Meckling that top executives compensation should be flipped from mostly cash to mostly stock, played a far more significant role in depriving workers of economic advancement. Lean management played a minuscule role, but it fed neatly into the prevailing economic and business wisdom of the late 20th century and early 21st century — to deprive workers of wage gains and non-wage benefits by separating them from productivity improvement.

And then, of course, there is the disdain that most top business leaders have for workers and their passion for automation — inevitable and necessary as it is — both of which in the United States have led to steady declines in the number of so-called blue-collar workers. This led to their migration into much lower paying service industry jobs (aided by a stagnant and disgraceful national minimum wage of $7.25 per hour; certain states have recently enacted higher minimum wages than the national minimum wage, which should be $25 per hour if it wages kept pace with inflation). Remarkably, there was no grand plan by industries or companies to absorb these good people into white collar jobs, get them into apprentice programs, shift them to other high-paying industries, or similar plan to avert underemployment and unemployment. Business leaders collectively said, “That’s not my job.”

Post-1980 were also major political and legal changes that reduced the number of unionized workers, made it harder for workers to unionize, and made it less attractive to join a labor union. (Note: I was a member of AAUP for 17 years). This weakened labor and greatly reduced the leverage unions had in the past to balance workers’ interests in relation to business interests. The decades of political rhetoric aimed at society to cast labor unions in a negative light was highly effective. So much so that when I asked a classroom of 25 undergraduate students (age 19 to 22) what they thought of unions, only three had a favorable view. That’s remarkable given that none of the students knew anything about the history of unions and how effective they were at shaping today’s work environment (higher wages, paid vacation, paid sick time, 8-hour workday, 5-day workweek, safeer working conditions, employee training and education, etc.).

So between the Friedman-Jensen/Meckling economic agendas, automation, and the weakening of labor (what the labor movement calls “union busting”), our revered genba workers suffered greatly, and Lean management helped out a just little bit to enhance their suffering through process improvement and the consequent need for fewer people. There is a cost to loving Lean, a cost that hits genba workers harder and longer than anyone else.

Needless to say, higher wages for genba workers have a huge positive knock-on effect in terms of quality of life, living conditions, housing, nutrition, healthcare, lower stress, family stability, savings, retirement, and overall economic growth. It is apparent that top Lean promoters and influencers have done little to highlight the problems I have touched upon, perhaps because they have been more concerned about their own business interests. I think that when our Lean history is written, it will be strongly criticized for doing little or nothing to better represent workers’ interests or engage with labor unions.

Lean was long ago subsumed by business interests. For example, the subtitle of the book Lean Thinking, “Banish Waste and Create Wealth in Your Corporation,” reflects the then outdated assumption that wealth would trickle down to genba workers. Fifty or more years have passed since the work of Friedman and Jensen and Meckling, and populist discontent is rising due to the fall in economic condition of so many people. That may not result in the changes that workers seek, as they still lack any real leverage to initiate changes that benefit their interests.

The cost of loving Lean is to lose focus of the purpose of Lean, which should parallel TPS and The Toyota Way, as opposed to “Create Wealth in Your Corporation.” In addition to customer focus, the purpose of Lean should fall along the lines of balancing human and business interests, reducing human suffering, thoughtful stewardship of resources, reduction of environmental impacts (negative externalities), and leaving the company and society in good shape for the next generation.

“Courage is the root of change.” — Elizabeth Zott

Follow the courageous example set by the Wiremold management team who shared the economic gains with workers.