“…all improvements come from something negative.” — Bob Rush

Prologue: Occasionally I get feedback from people who perceive my work as being negative, rather than as a positive pathway forward to “get out of the pit,” as W. Edwards Deming said. They get that perception mainly from my LinkedIn posts and perhaps from my recent books. When it comes to social media, I think it is especially important to challenge people’s thinking about the problems that the Lean community faces to that we can improve. But some people don’t like that. When it comes to books, I long ago decided that it was far more important to work on the big problems, rather than write me-too books about Lean tools.

Remember, there are thousands of people who consistently write about the positive aspects of Lean management, but only a few people who think and write critically about Lean looking for ways to improve it. Few offer tough-minded realism and are not afraid to publicly share their disdain for nonsense. There is no need for me to do what everyone else does, but there is great social pressure to do so — which I have long rejected. Progress always slows down or is halted when everyone thinks the same way and does the same things.

As far as negativity, you may be surprised to learn that 85 percent of the books and journal papers that I have written, as well as my two decades of Lean leadership training and teaching, have focused on the positive — how to succeed with the current forms progressive management, TPS/Toyota Way and Lean. So while “negative” may be the perception, the facts say something different.

What follows below is a recent exchange with a veteran Lean professional. The feedback is similar to many that I have received in the past. The exchange has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Person B: The overwhelming aspect of your well researched and well documented ideas seem so negative. Your negatives seem to well outweigh your positive ideas on how to find a way for people to attempt to make changes that, perhaps over a timeline that they may never see, will amount to some change. Your consistent theme of the seemingly eternal “Institution of Leadership,” while seeming accurate, will take more centuries to turn the Titanic around. People need more near term hope and encouragement to create, unfortunately slowly, the eventual tsunami, (hopefully), that will see change in respect for people. I dare say, that in this continuing world of confusion and warfare and combativeness for religious and political reasons, allow also the continuous ‘warfare’ of the old management style versus the goal of ‘respect for people’.

Bob Emiliani: Key characteristics of my work include: 1) to not follow the herd of Lean/CI cheerleaders — there is an overabundance of those who fulfill that role; 2) to go where the research takes me, and 3) to not seek approval for what I do or don’t do. If you recognized the totality of my work, you would find that the majority of it (~85%) supports TPS+TW/Lean/CI, while my recent work is directed towards figuring out why most top leaders — centuries ago and still today — resist, reject, or ignore progressive management. A willingness to accept those findings, rooted in historical facts, is the key to finding new ways to gain greater acceptance of progressive management among current and future leaders. It is not “negative,” as you mistakenly characterize it, but a positive contribution to the body of management knowledge. A failure to accept those findings and act on them likely will forever relegate Lean to a niche management practice with little hope of gaining a broader audience among senior leaders no matter how hopeful people are for change. We must admit that the past efforts have not worked well, and new, so-called “negative” information, provides a pathway forward.

Person B: Bob, I won’t argue that I was off, and that 85% of your output is positive. My feeling, that it was almost the inverse, or even more so, is what is important. What do I ascribe as to my misapprehension, without actually tabulating it? I would say that your negatives drown out your positive messages. At least that is my impression. So, in reading some of your comments, that mainstream CI tends to relegate your inputs as being negative, or worse, unimportant, perhaps it is because they have the same perception. I know you are attempting to make a difference, I might humbly suggest that perhaps working on that aspect might get your true message across to more people? Just a thought. I do respect your work, but if it’s not heard by enough or more, then is it not just shouting on the street corner? That’s not how you should be perceived, but how to change that is the point I’m suggesting should be reviewed.

Bob Emiliani: Research that finally explains why — throughout history — most leaders resist, reject, or ignore progressive management is a huge positive development! Most of the top Lean promoters and influencers don’t like someone who speaks the truth with respect to why Lean transformation has been so difficult to achieve. They’re rather disenfranchise me than learn from my work. So there are two problems with that: 1) they disrespect people , the Lean community, by keeping them in the dark about advances in knowledge, and 2) not “walking the talk” with respect to problem-solving, scientific thinking, etc. They mislead dedicated people. That’s far worse than what I do. You see this narrowly as a perception problem, I see it as a much larger problem of not serving the Lean community; not engaging the Lean community in overcoming its existential problem. In doing so they avoid “Continuous Improvement” of Lean itself and forego learning. A lot of this simply boils down to the fact that the top Lean promoters and influencers are generally intolerant of anyone and any information that upsets their Lean vision of success (and consequently, the business of Lean). That surely is “negative” to the principles “Continuous Improvement” and “Respect for People.”

What follows below is also similar to feedback that I have received in the past. In an email several months earlier, this same person said:

Person B: In your online comments, you come across as throwing a lot of blame on others. In the case we are currently talking about, the authors of The Machine That Changed the World, who missed important issues on respect for people. One of the “wastes” that the Lean community misses, is a very simple but insidiously one: blame. I see you utilizing that in blaming the authors for missing the respect for people for many years. While that is correct, blame doesn’t provide answers. It also, I believe, is one of the major reasons that Western Culture misses out on how to manage and problem solve. The first reaction is always blame. In most, if not all, business cultures, blame is there. It starts when we are all children and taught in school and reinforced everywhere, and at work. That is disrespect for people. Finally, you point out, rightly, that the overall lean community has missed the aspect of “respect for people” from the start of Lean. Womack et al were successful in capitalizing on their publication and creating a marketing and consulting group to bring attention to it. The others that you mention, rightfully so, did not create a bandwagon to get attention. Unfortunately that is often the case, of great ideas etc. Thanks for listening.

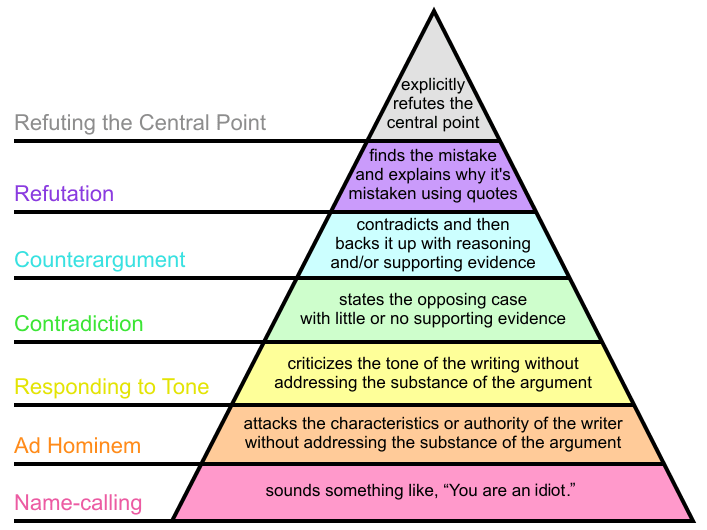

Bob Emiliani: Many people misconstrue blame with simply pointing out the facts. I criticize Womack and Jones’ work, not them as people (no ad hominem attacks — I have met them both; they are quite nice). Not long ago, pointing out facts was not comprehended as blame. But, today it is. That is something I cannot correct. My criticism of Womack and Jones’ (and others’) work has always been at the top of the pyramid. It is noteworthy that when Lean people criticize my work, it is nearly always at the bottom of the pyramid (bottom four layers, tone in particular). Occasionally someone does present a counterargument, but never has anyone engaged in refutation, to my great surprise. As far as blame and providing answers to blame (as well as “Respect for People”), my large body of work covers these in extraordinary detail. My first published paper on this topic was titled “Lean Behaviors” (1998). It cited blame as one of the many forms of “behavioral waste” that must be eliminated. Much of my subsequent work (to 2011) was based on that paper.

Comment: Over the years, I have received this kind of “help” from many people. The help they should be giving is to themselves, not to me. The reality is that Lean is handcuffed to business and so it cannot escape the deeply ingrained business mentality of success orientation, and is thus averse to anything negative — problems, of all things! Therefore, the challenge lies with Lean itself, to free it from the business mentality that weakens it and re-engage with the industrial engineering mindset that it long ago left behind. The plain reality is that the top Lean promoters and influences who have strayed far from the foundation of Lean, which is TPS and TW: industrial engineering, critical thinking, flow, JIT, creative problem-solving, and kaizen

Analysis: The perception of negativity and of being disrespectful makes me a jerk in some (many?) people’s eyes. I say things that people in Lean world do not want to hear. I ask uncomfortable questions because they need to be asked. I share my uncomfortable work with others because I think they need to know the work to improve. I value the truth, and as a former academic (and current professor emeritus) my business is truth. There are lots of things in life that are true and which makes us uncomfortable, and that can produce an unhealthy social response — niceness.

There is great social pressure in Lean world to be nice, which often manifests as censorship of others and usually comes into conflict with the truth. I think truth is more important than complying with people’s fixed or changing views of what being nice (positive) means. Social pressure to be nice generates passive-aggressive hostilities which have the knock-on effect of producing confusion and a lot more errors (untruths).

The people who most strongly voice support for Lean management are almost always the ones most committed to censoring the truth (self or others) and least receptive to improvement. Efforts to denigrate, discredit, or stigmatize the “bad people” (iconoclasts) makes Lean look more like a cult of blind and complacent enthusiasts than a open-minded science-based system of management. The iconoclasts, the jerks, and their negativity are necessary for progress.