Chief Confusion Officer (CCO) is how I think of the CEOs who persistently send out the mixed message that they want Lean management yet they restrict employees’ ability to practice Lean in such as way as to produce tangible business results. In the post “Junk Lean,” I said:

Unfortunately, Lean professionals get squeezed by the need for business results and leaders shutting down the kinds of improvements that many (not all) Lean professionals know would produce business results. They must contend with top leaders’ hallucinations that the business results they expect Lean professionals to deliver can be achieved without any of the big changes that are well-known as being required to produce the results.

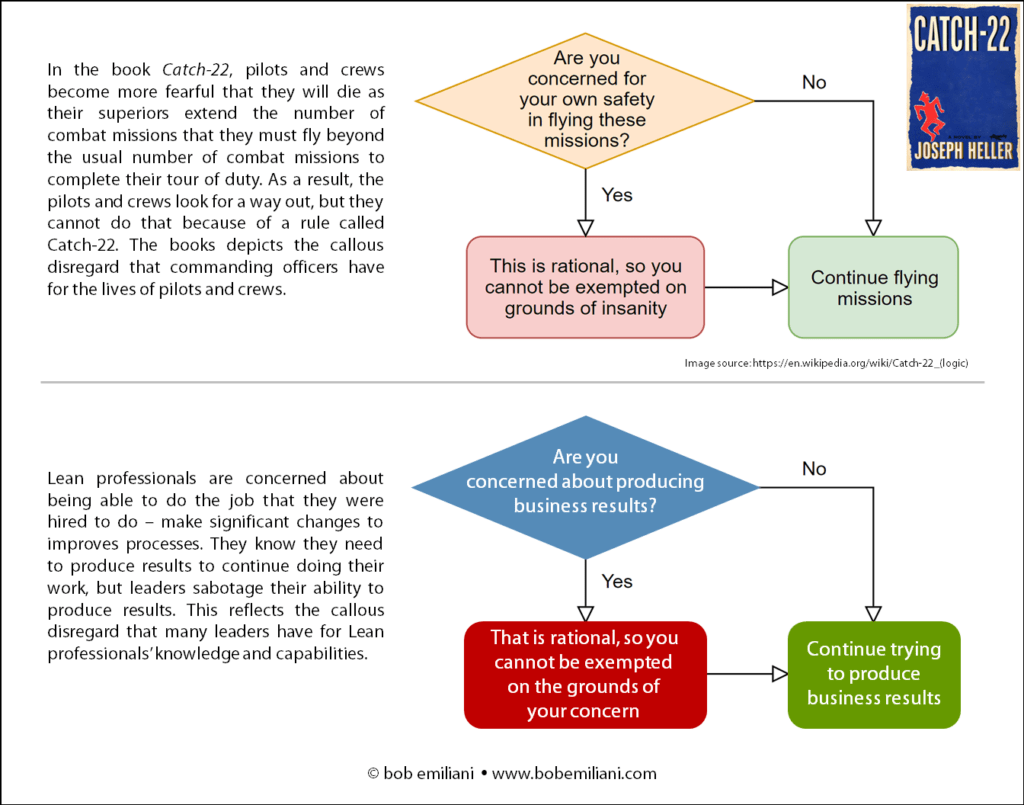

Many Lean professionals are caught in a “Catch-22,” a phrase coined by author Joseph Heller in his 1961 book of the same name that describes a no-win situation. In the context of Lean, it describes business leaders who, purposely or not, sabotage Lean professional’s efforts to produce business results. The image below describes the logic of Catch-22 for Heller’s book (top) and Lean (bottom).

Most top leaders see benefits in creating a state of confusion in the company, and not just with Lean. A perpetual state of confusion keeps employees sharp (results-focused), aware (focused on numerical targets), engaged (ready to firefight), and on-guard (fearful), or so leaders’ thinking goes. The current wave of tech layoffs make the unmistakable statement to the remaining employees that “We’re in charge, and what you want [such as work-from-home] is entirely at our discretion. You have no control.” So creating a state of confusion is typically intentional, notwithstanding the usual chaos and confusion that is integral to classical management.

To Lean professionals and others, it defies technical logic. But it is fully consistent with business logic. With technical logic, you would say, “Well, if we’re not serious about Lean, then let’s just admit it and move on.” But with business logic, the CCO will say, “I’ll assume that the incremental gains we can get in cost reduction, sales, profits, market share, and quality will offset the costs of hiring a Lean team to drive results.” But alas, the CCO realizes, sooner or later, that the Lean team can’t deliver the expected results no matter how intensely they are micromanaged. And top leaders always reserve the right to pull on the one thread that leads to the complete unraveling of Lean.

The Chief Financial Officer is often more like the Chief Blocking Officer. The combination of holding the purse and not understanding Lean management means Lean will be immediately bureaucratized and bean-counted. Lean teams will have to present detailed plans to leaders and get permission every time they want to do their work, will be required to make financial commitments, and will be held accountable for results that they likely can not achieve. The “just do it” spirit of kaizen will be killed off from the start, and Lean teams will become frustrated and quickly develop expertise in check-the-box compliance.

The restrictions imposed by leaders on Lean professionals follows from the logical fallacy “slippery slope” or “give an inch and they’ll take a mile.” There is a preconception that there will be a succession of events that will result in bigger problems, erode leaders’ status, rights, and privileges, or both. Their evidence for this is non-existent, of course (a benefit of having high status), but that does not preclude application of any logical fallacy for one’s convenience — in this case, to limit the scope and magnitude of change. As is commonly the case, leaders talk endlessly about “excellence” but typically fail to create the culture necessary to produce it. Some things are more important Lean.