It appears that I introduced a new term (again!) in a recent blog post: “Junk Lean.” What is Junk Lean? The phrase expresses the gap between Lean management understood as a generic term for Toyota’s production system (circa 1988) and how Lean is practiced in reality as popular problem-solving tools (2024). You can call it a theory-practice gap or a TPS practice-Lean practice gap.

Here is how I describe the gap:

- Not understanding the differences between change, improvement, and progress

- Subscribing to, if not defending, misunderstandings and misapplications of Lean

- Using Lean tools without any clear business objective or goal in mind

- No connection between the use of Lean tools and Just-in-Time, flow (within a process and between processes), improving quality and productivity, and reducing the order-to-cash cycle

- Thinking of Lean the same way one thinks of the 7 QC tools — as a few more basic problem-solving tools

- Insufficient focus on the details of work

- Lack of creativity, especially in relation to the invention of devices and the reconfiguration of people and equipment to improve processes

- Solving problems slowly, as is done with classical management

- Too much nebulous learning outcomes from using Lean tools and not enough development of know-how

Have I left anything out? Maybe you can think of others.

Let’s connect Junk Lean to the unpleasant recurring phenomenon of Lean professionals getting laid off. Business leaders do this for three main reasons. After some period of time, they:

- Do not see the business results they had hoped to see (empty business results from Junk Lean, analogous to empty calories from junk food)

- Think Lean has become part of the company’s DNA

- Get annoyed with Lean professionals as they become increasingly critical of company leadership and management practice

Recall that in recent times, influential people would frequently proclaim “Lean is all about learning.” No it’s not. It is about developing the know-how, through trial and error efforts, to make the kinds of improvements to work (and human-machine and machine work) that produces business results. Characterizing Lean as being “all about learning” has the unintended effect of further widening the gap between TPS (1988) and Lean (2024).

Who are you doing Lean for, yourself or your employer? It is for your employer. That means you have to be able to do two things at once: produce the business results that top executives want and gain the cumulative know-how that will produce future business results.

Unfortunately, Lean professionals get squeezed by the need for business results and leaders shutting down the kinds of improvements that many (not all) Lean professionals know would produce business results. They must contend with top leaders’ hallucinations that the business results they expect Lean professionals to deliver can be achieved without any of the big changes that are well-known as being required to produce the results.

This consigns most Lean professionals to Junk Lean, which limits their acquisition of know-how (as distinct from learning) and produces the perpetual risk of sudden unemployment. Add to that “Fake Lean,” which describes organizations that practice “Continuous Improvement” without “Respect for People,” and we have what seems to be an impossible situation.

All of this combines to produce a situation that is best described by the iconic phrase, “Catch-22” from the great 1961 novel of the same name written by Joseph Heller, which describes a no-win situation, one that most Lean professionals face. Catch-22 is defined as “a problem for which the only solution is denied by a circumstance inherent in the problem or by a rule.” In this case, the circumstances inherent to the problem and rules that leaders place on Lean professionals usually put them in a no-win situation.

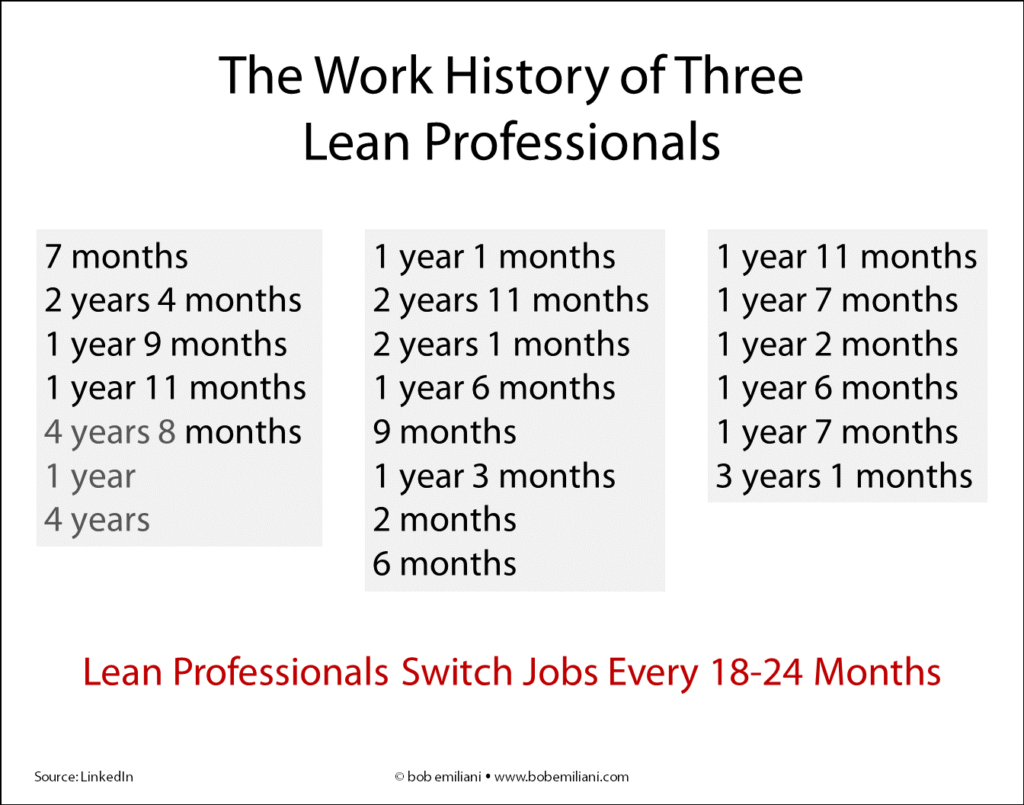

Because of the contradictory circumstances and rules, Lean professionals soon voluntarily leave for another job or get laid off — only to find the contradictory circumstances and rules in their next job. The result is a fragmented work history.

It is remarkable how this situation has evolved over the last 35 years. The fight over the integrity of Lean between Lean movement leaders and business leaders that should have happened never happened. As a result, Lean drifted from a generic term for Toyota’s production system in 1988 to its practice in 2024 as popular tools for basic problem-solving.

So what can be done?

- You can learn the circumstances inherent to the problem and rules, and with that knowledge think of many new ideas to try

- You can accept the situation as-is and not worry about it

- You can move on from Lean

- You can maintain your commitment to Lean but wait until the business environment has changed such that business leaders see the need for Lean management, not just Lean tools

These may not be great options, but at least there are some options. Maybe you can think of others.