Lately, I have been thinking more about these words I wrote in the blog post “Lean Zombies:”

When one looks at all the great management thinkers over the last 100 years — from Taylor, the Gilbreths, to Follett, Mayo, Deming, Ohno, Drucker, Argyris, Kanter, Senge, Schein, etc. — they have all had senior leaders’ attention (and lucrative consulting work) at one point or another. But whatever they may have taught executives has proven to be largely non-transferable from one generation of leaders to the next. All of this great thinking has proven to be largely ephemeral; curiosities that do not have staying-power. Most top business leaders lead the same way that leaders before them led, for generations.

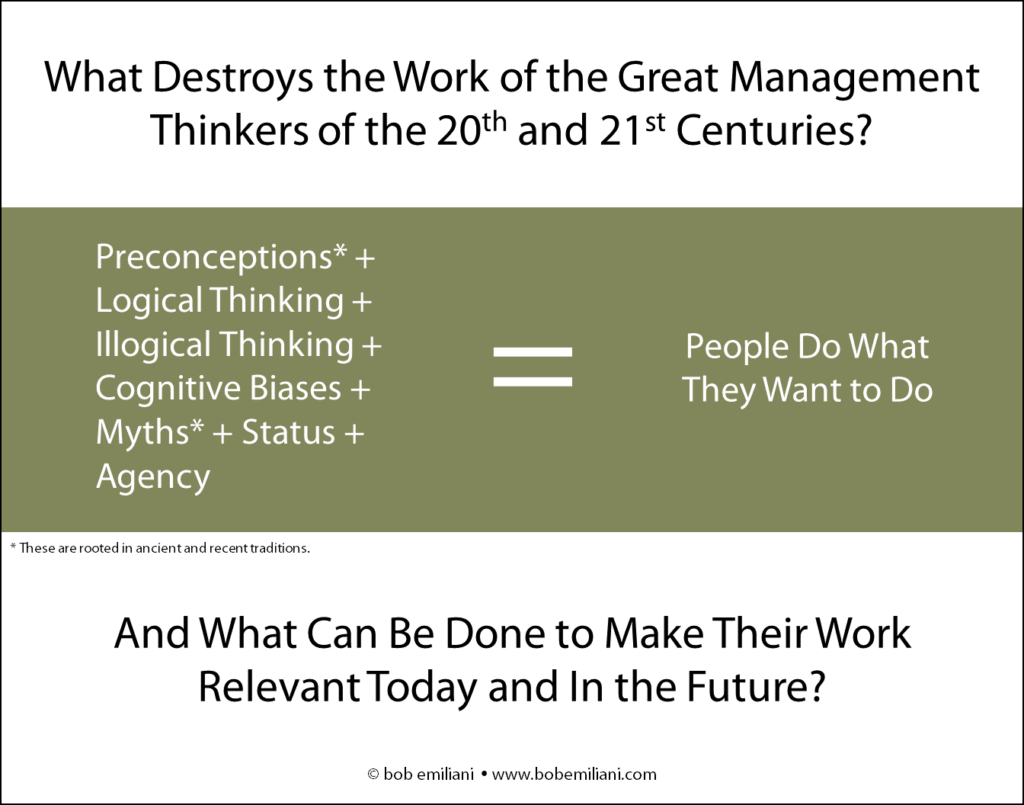

So the question is: What destroys the work of the great management thinkers of the 20th and 21st centuries? What is the mechanism that causes their work to have no long term influence among top business leaders? Assuredly, the work of the great management thinkers remain alive with some people such as salaried professionals and the academics who study leadership and management. But to what end if top business leaders remain indifferent to better ways of leading and managing organizations? Apparently the need still does not yet exist for top business leaders to employ better ways of leading and managing organizations.

From the perspective of my work experience and research, the causal mechanism looks like this:

The sum of the equation equals the general case of “people do what they want to do,” which includes the special case of business leaders also doing what they want to do. If asked to assign percentages to each item on left side of the equation, I think it would be as follows:

20% Preconceptions

10% Logical Thinking

10% Illogical Thinking

15% Cognitive Biases

15% Myths

20% Status

10% Agency

While people may be enamored with the idea of simplicity, in the real world they make things complex. That should be no surprise given the weight of preconceptions, illogical thinking, cognitive biases, and myths. An example is the leadership routines associated with classical management. They tend to be very simple, such as: “I’m the boss, do as I say,” blaming people lower in the hierarchy for problems, performative acts of interest in the plight of others, making unreasonable demands, ostracizing those who disagree, making credible-sounding excuses for problems, etc.

These leadership simplicities lead to great complexity in terms of the efficient and effective operation of organizations. Meaning, the ability to quickly recognize and respond to changes in market conditions, new competitors, shifts in customer demand, improving productivity, employee engagement, generational changes in employees wants and needs, the concerns of society, etc. This is what the great management thinkers’ inventions sought to correct, but, unexpectedly, the inventions did not create any widespread necessity for their use by leaders.

The ancient Greek philosopher Plato wrote “our need will be the real creator,” which over time turned into the proverb “necessity is the mother of invention.” However, the “inventions” of the great management thinkers over the last 100 years preceded necessity from the perspective of most top business leaders over that same span of time. The causal relation — necessity leads to invention — is based on the preconception by the great management thinkers that all change results in improvement. The proverb thus suggests that top business leaders, en masse, will accept improved ways of leading and managing organizations when the need arises. When that happens, leaders will likely take credit, or be given credit, for “inventing” that which was previously invented by the great management thinkers over the last 100 years.

The early 20th century sociologist Thorstein Veblen turned Plato’s proverb around. He said “invention is the Mother of necessity,” which changes the sequence of cause-and-effect: invention leads to necessity. An invention generates the necessity of its use, often far beyond that which is actually needed, and it likely generates many new problems due to its very existence. Thus, inventions do not always result in improvement, despite it having altered the status quo. For example, the invention of advertising, the automobile, social media, and artificial intelligence preceded necessity, but once invented they soon became a necessity. But these inventions also resulted in many new and different types of problems that everyone must contend with, which in turn create new inventions that become adjacent necessities.

The amount of social, economic, and political changes brought about by inventions varies. In the case of the great management thinkers, not much change has taken place as a result of their work. Changes in leadership and management practice are regulated by top leaders, providing only the minimum that is required to prevent higher costs or disruptions. Top leaders’ decision as to the “minimum required” is based roughly on the percentages shown above, principally out of their need to maintain order, power, wealth, status, rights, and privileges.

This leaves us with an important question: What can be done to make the work of the great management thinkers relevant today and in the future. For today, probably not much. For the future, it will depend on either how acute the need is for inventions (past, present, or future) to better lead and manage organizations, or whether inventions to better lead and manage organizations will generate its necessity. The causality could go either way. But, as we have seen with Lean management, which preceded necessity, its invention did not generate the necessity of its use in the way that Jim Womack had hoped.

Caveat venditor.