In Part 1, I said that the people who helped cause the financial meltdown beginning in 2008 graduated from top schools and had high grade-point averages. Generally, one finds the same is true for other big failures such as: Boeing’s 787 development program, Baxter’s contaminated heparin blood thinner, General Motors’ bankruptcy, Johnson & Johnson’s drug and medical device recalls, Nokia’s unproductive R&D investments, compounding pharmacy’s fungal meningitis contamination, JC Penney’s market decline, Toyota’s quality problems, the U.K. Lean government initiative (HMRC), etc.

These outcomes are distressingly common and indicate at least three massive failures in higher education. Specifically, the failure of 40 or so faculty in an undergraduate program to:

- Teach students how to think critically

- Understand the different forms of illogical thinking and decision-making traps

- How, when, and why to do research

This suggests that it may be far more important to evaluate professors than students. Once students leave the university, nothing can be done to guarantee that they apply what they learned. But, we can improve how professors teach these three incredibly important skills to students and do so in ways that make them feel poorly educated and irresponsible if they do not apply what they learned post-graduation.

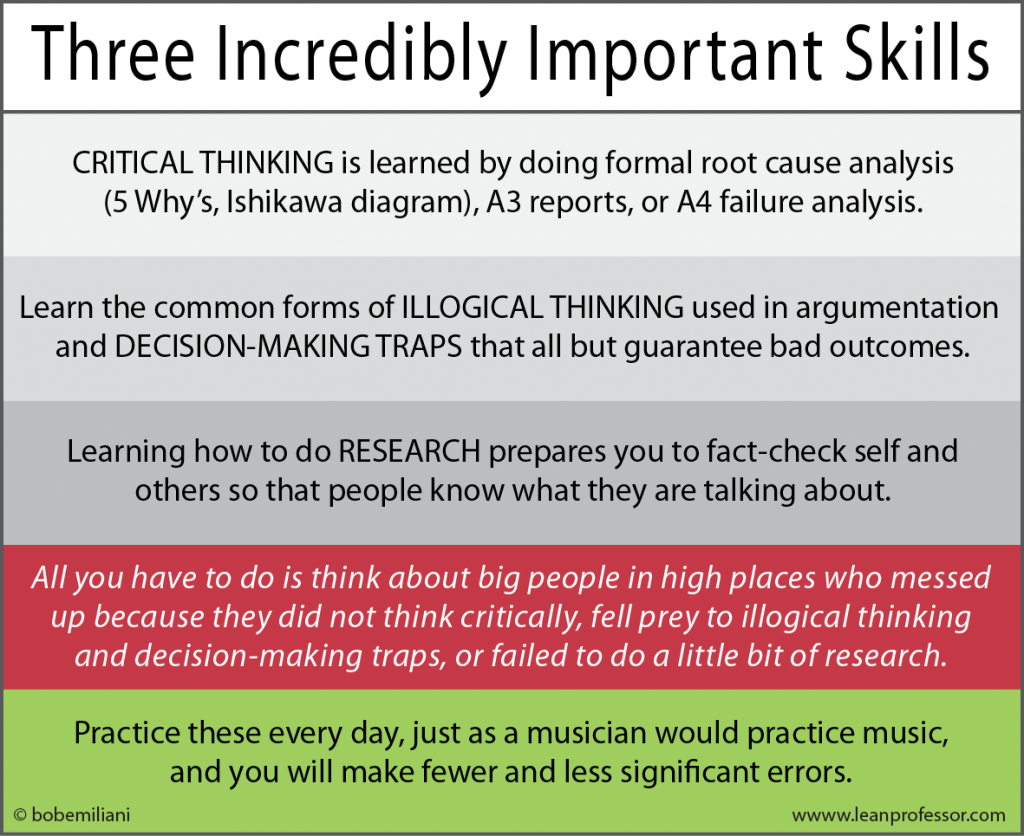

Professors often characterize critical thinking as the identification of alternative solutions to problems. That’s not critical thinking; that’s guessing at the causes of problems. To teach critical thinking, faculty must engage students in formal root cause analysis (5 Why’s, Ishikawa diagram), A3 reports, or A4 failure analysis.

Good grades, especially from prestigious schools, often lead to overconfidence in one’s decision-making capability and the acceptance or proffering of illogical arguments. Faculty should teach students the most common forms of illogical thinking used in argumentation and decision-making traps that all but guarantee bad outcomes.

Most students do not view the research they did in school as relevant to the real world. The failure to fact-check and think critically often means they do not know what they are talking about and create or perpetuate misconceptions (such as what Just-In-Time is). Faculty can provide students with practical examples of big people in high places who messed up because they failed to do research, think critically, or fell prey to decision-making traps.

Students will benefit only if a systematic approach is taken by faculty to teach these three critical skills. Repetition of the three critical skills across most courses, rather than one or two courses, will be required in order for students gain effective working knowledge of their use. Practical examples of the failure of people to use these three important skills abound in every discipline.

The desired outcome is for students, post-graduation, is to be able to:

- Do effective formal root cause analysis when confronted with a problem and identify practical countermeasures.

- Avoid proffering illogical arguments, easily identify illogical arguments made by others, and skillfully avoid decision-making traps.

- Do sufficiently detailed research to understand an idea or concept that they seek to undertake, to help assure correct understanding and application.

In sum, perhaps evaluations are better directed at faculty than students, to help assure that graduates have learned the skills that, if put into practice, will help them make fewer and less significant errors. The visual control, below, may be helpful to students as a reminder of what to learn and practice.