Instead of poking fun at anything intellectual, why not get over this prejudice by recognizing the intellect as simply the instrument used by the mind.

The Creative Workman

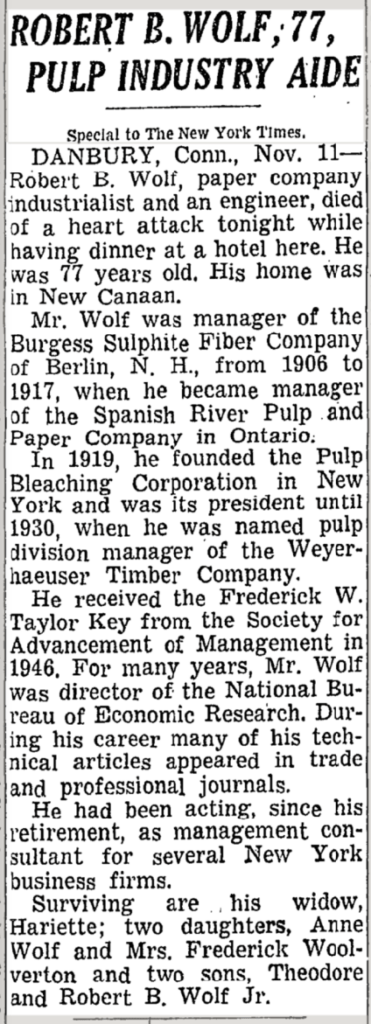

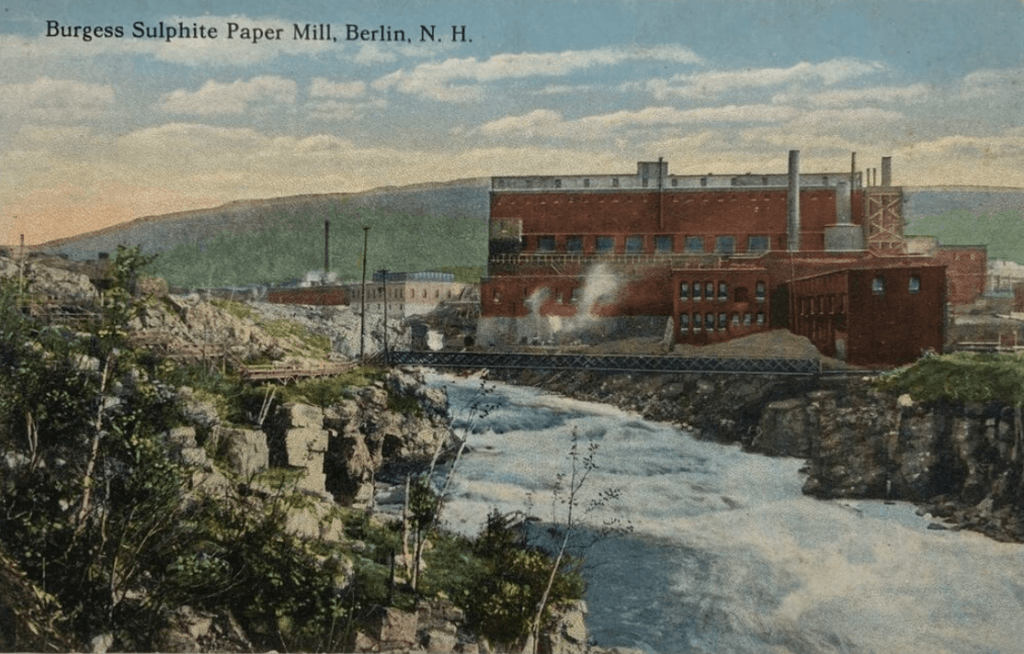

Robert B. Wolf, received a bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering from Delaware College (today, University of Delaware) in 1896 and a master’s degree in mechanical engineering, also from Delaware College, in 1916. He started out as an assistant engineer for construction and maintenance and later as superintendent at the Sulphite Pulp Mill. Wolf was involved with pulp and paper machinery design and construction, and later became a manufacturing manager for various pulp and paper companies in the northeastern United States and Canada in the early 1900s. Subsequent to his career in industry, be started a successful consulting engineering company, R.B. Wolf Company of New York (33 West 42nd Street, later at 42 Broadway, New York, N.Y.), a designer and builder of pulp and paper machinery. Wolf was well-known and highly regarded in the pulp and paper industry, and his writings on leadership and management (shown below) brought him acclaim in other manufacturing industries.

In the early 1910s, Wolf was associated with the Scientific Management movement. But he had substantially different views about worker’s intelligence and creativity, and management’s role in bringing out those attributes, compared to Frederick Winslow Taylor and some of his associates (learn more about Scientific Management here and here).

After Frederick Winslow Taylor died in early 1915, the principal leaders of Scientific Management soon moved decisively in the direction of greater worker engagement, including union members, by appealing to their intelligence and creativity. The primary influencers for this change in thinking were Lillian M. Gilbreth (consultant), Robert G. Valentine (“Industrial Counsel”), and, especially, Robert B. Wolf (Manufacturing Manager) — all three of whom proved their ideas in real-world industrial practice.

Despite his thinking and management practice being far ahead of its time, Wolf succeeded in influencing not just key members of the Scientific Management community previously aligned with Taylor’s thinking, but also labor union and industry leaders. Wolf’s hugely insightful writings shaped the course of action for progressive leaders in the late 1910s and 1920s. However, much of that good thinking and good practice was undone by the early 1930s due to the Great Depression, because in tough times managers reverted to the old ways of doing things as they typically do.

The idea to utilize workers’ intelligence and creativity lay mostly dormant until Toyota revived it as part of their effort to catch up to Western automakers, principally through the kaizen method. It is not known if Toyota managers read Wolf’s writing, but similarity it and Toyota’s way of thinking, as exemplified by Taiichi Ohno and other engineers, is unmistakable. Additionally, Toyota managers were surely familiar with Lillian Gilbreth’s 1914 book, the Psychology of Management.

Overall, it is very likely that Toyota managers were close readers and observers of the thinking and practices of the leading industrial nations at that time, which were USA, England, France, German, and Russia. Without Scientific Management, which led to the creation of Industrial Engineering (inclusive of human relations), TPS would not exist. So, surely they knew of Scientific Management and likely read much of the available literature.

Rare is the manager who does not fall prey to the preconceptions that contaminate their field of work as well as their leadership social group, and who instead exhibit the type of deep curiosity, thoughtfulness, independent thinking, and management capabilty evident in Wolf’s work. I am excited to bring these wonderful articles to you. Management history matters.

Below are seven of Wolf’s most important and influential writings that describe the amazing work he did at Burgess Sulphite Fibre Company, which I briefly preface as to their significance then or now. While these writings are more than 100 years old, they remain relevant today given that most organizations are still classically managed and broadly fail to utilize the intelligence and creativity of the hourly and salaried employees. Every current or aspiring CEO, manager, and Lean practitioner, should download and read all seven of these important papers — marking them up or taking notes — and proceed to implement these practical ideas.

It is a tragedy that Mr. Wolf’s important, forward-thinking writings have been lost to time. Please help bring his work back to life by sharing this blog post with as many of your colleagues as you can.

It is unnatural for men to work in a negative and destructive manner and the fact that so much of this sort of work is done is not so much a reflection on the individual workman as it is upon the manager who has failed to create an environment in which a man can work intelligently.

The Creative Workman

INDIVIDUALITY IN INDUSTRY (1915): In his 1978 book, Toyota Production System, Taiichi Ohno wrote about parallels between a company and the human body, and described elements of TPS that form an “autonomic nervous system” (see 1988 English edition, pages 29, 45-47). Remarkably, Robert B. Wolf’s 1915 paper, “Individuality in Industry,” described a company the same way, but in far greater detail than Ohno-san. Specifically, Scientific Management, done correctly, installs “a subconscious control” in the company. The same is true for TPS via kanban.

MILL EFFICIENCY (1917): I was about to give up searching online for a photograph of Mr. Wolf, when I luckily found this article and a photo of him, shown above (likely around age 40)! In another very interesting paper, Wolf describes how he was able to achieve greater productivity by understanding the workman’s point of view and gaining their cooperation for improving equipment and processes by using scientific methods rather than the traditional rule-of-thumb. He says: “[improving productivity] is a very definite, vital, human problem, and requires a constant development of the intellect of the men in the organization. In other words , it is an educational process and the function of the management becomes primarily educational in nature. It is more a question of leadership than of compelling obedience.”

THE CREATIVE WORKMAN (1918): This paper is a tour de force of logic, wisdom, and deep insights. Most of the sentences in this paper could easily be categorized as notable quotes! There is a remarkable parallel between Wolf’s conception of the workman’s intelligence and creativity and how Toyota leaders view the workman’s intelligence and creativity and employees — which today is refreed to as “developing people.” It is notable that almost the entirety of the discussion of Wolf’s address (see last two pages) was in relation to the technical details of paper manufacturing, largely ignoring what Wolf had to say about managers and the workmen. The early days of study of TPS and Lean likewise largely focused on technical details and missed the most important aspects of the manager and worker relationship.

NON-FINANCIAL INCENTIVES (1918): In this paper, Wolf seeks to alter the long-prevailing businessman and Taylorist view that the only way to increase worker’s output is to offer financial incentives. Instead, Wolf showed how his company was able to achieve increased output and better quality products by providing process information to workers so that they could better understand their work and thus intelligently and creatively improve their work. Today, we can say that most workers have the information they need — likely more than the need — but management does not develop the curiosity and spirit needed for employees to autonomously improve processes.

SECURING THE INITIATIVE OF THE WORKMAN (1919): In this paper, Wolf builds unpon the ideas presented in his 1915 paper, “Individuality in Industry.” He describes the individuality of the industrial organization in relation to the individuality of the workman. The central idea is to develop individual initiative, rather than repress it. Management must not do thinsg that prevent employees from exercising freedom to use their brain — their intelligene and creative power — in the course of doing their job.

MAKING MEN LIKE THEIR JOBS (1919): This is a two-part article seems to be a capstone to Wolf’s earlier writings. The publisher’s note at the beginning of the first atrticle says it all: “This article, one of the most important which SYSTEM has ever published, outlines the philosophy of work as applied in a practical manner to the daily direction of workers. Mr. Wolf shows why men leave, why they are dissatisfied, why they take no interest in their work. He traces the causes and then shows obedience of fundamental laws. Then he that the surface indications are due to a disexplains how in his own work he has obeyed these laws, and describes the remarkable results attained. He cuts under the surface and gives ‘reasons why.’ We all know the surface, but no one, so far as the editors know, has worked out so completely as Mr. Wolf, the causes. It is not an article to be merely skimmed through; it is to be read and reread, for it unfolds a whole philosophy of work. And every executive knows that today the human problem is the biggest. Mr. Wolf is manager of the Spanish River Pulp and Paper Mills, Ltd.”

Some of our so-called learned men exhibit the least amount of intelligence and therefore in reality have the poorest education… the unthinking man is not a responsible man.

The Creative Workman

Click here to download a .pdf file containing all seven of Wolf’s papers.

Intelligent workers and intelligent employers are more interested in locating causes than in tabulating results.

Making Men Like Their Jobs, Part 1

In addition to having a remarkably accurate view of reality, Mr. Wolf is endlessly quotable!

Wolf spent the latter part of his career earning a living as a consulting engineer to the pulp and paper industry. Wolf was also a part-time lecturer at The New School for Social Research in New York City speaking, among other things, on the topic of “The Application of American Principles of Government to Industry.”