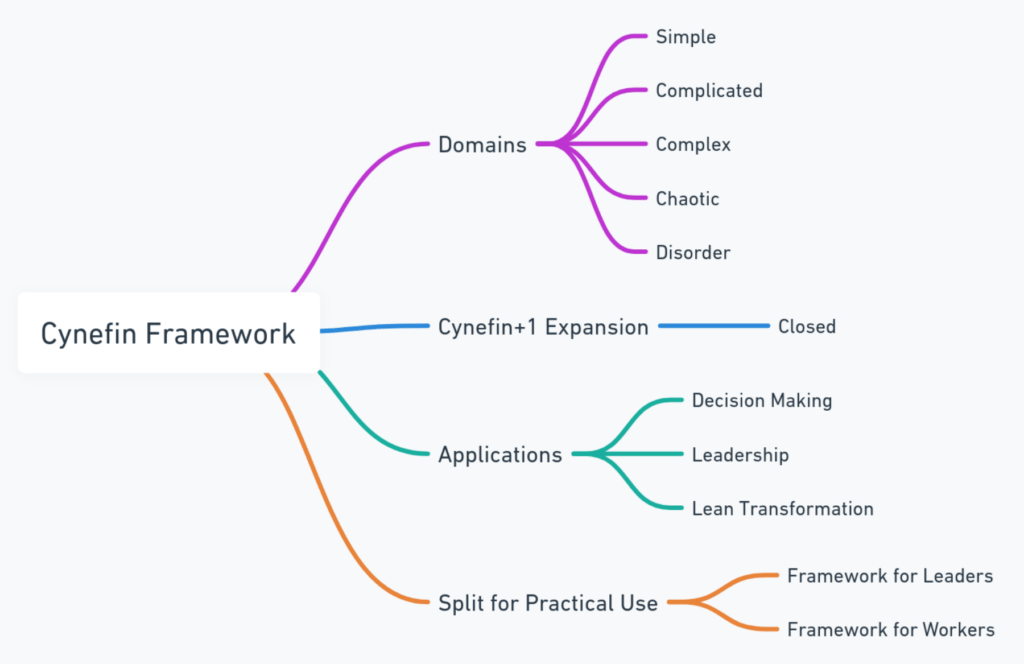

Summary (AI Generated): This article discusses the Cynefin framework, a decision-making framework for leaders based on complexity science. It critiques the framework’s ontological assumptions and suggests improvements to better reflect leaders’ realities. It introduces a modified version, Cynefin+1, which adds a “Closed” domain to address the institutional power dynamics of leadership. The article argues for splitting Cynefin into two frameworks: one for leaders and another for workers, to align with their distinct realities and decision-making needs.

PART 1: In November 2007, the world was introduced to the Cynefin (pronounced ku-nev-in) “sense-making” framework in a Harvard Business Review article authored by David Snowden and Mary Boone titled, “A Leader’s Framework for Decision Making” (where a “framework” is a system of rules to make decisions). The online version of the article contains these words at the start of the article’s summary:

Many executives are surprised when previously successful leadership approaches fail in new situations, but different contexts call for different kinds of responses. Before addressing a situation, leaders need to recognize which context governs it—and tailor their actions accordingly. Snowden and Boone have formed a new perspective on leadership and decision-making that’s based on complexity science. The result is the Cynefin framework, which helps executives sort issues [problems] into five contexts: Simple… Complicated.. Complex… Chaotic… [and] Disorder.”

(Note that the framework has undergone many revisions or updates since 2007)

The framing of “executives” in the summary tells us that organizations are the context for the Cynefin framework — businesses, not-for-profits, government, and non-governmental organizations. Organizations, of course, have leaders, from supervisor to CEO and the board of directors (or their equivalent in political contexts). In these contexts, a leader is anyone who has authority over people and things (i.e., resources used to fulfill the organization’s purpose), with authority being granted by the top leader or the board of directors in accordance with corporate bylaws, policies, and rules both written and unwritten (or their equivalent in political contexts). Additionally, the context for the existence of Cynefin is action-oriented — for leaders to acknowledge the existence of problems and make decisions about problems with the wholesome intent to correct problems.

Organizations have problems internally or externally. The Cynefin framework aids in sense-making to assure that the context of the problem is understood prior to making decisions or specifying possible solutions. This is to avoid the common mistakes of:

- Jumping to ineffective solutions

- Applying simplistic solutions to difficult problems

- Dismissing known solutions

- Reinventing solutions

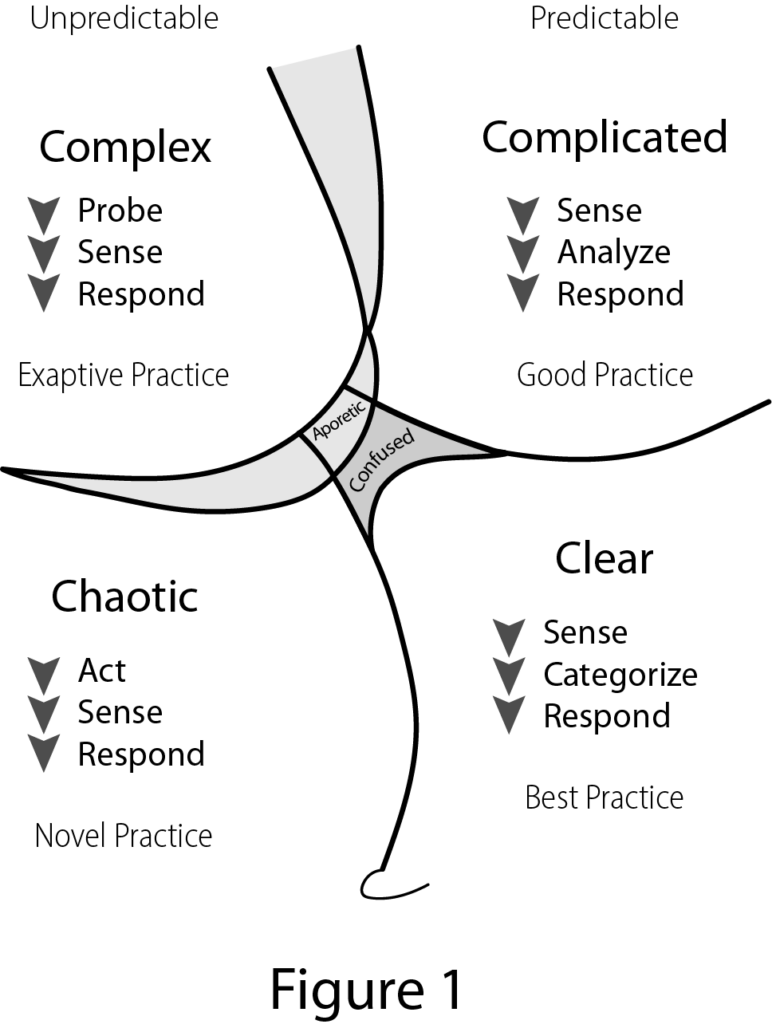

Figure 1 shows a recent version of the Cynefin framework (click here for additional information about the Cynefin framework, here for descriptions of the “Aporetic” and “Confused” domains and other definitions, and here for more comprehensive explanation). The squiggle above the word “Figure 1” is called the “Cliff.” It is the boundary (liminal line) between the Clear and Chaotic domains, and represents leaders failing due to “excessive confidence in the applicability of rigid constraints.” It is the “Zone of [leadership] Complacency.” In other words, leaders get complacent and things go awry, so they then have to contend with chaos (“no causal relationships between parts are knowable”). On the surface, Cynefin does indeed appear to be as advertised: “A Leader’s Framework for Decision Making.”

But think a little bit more and dig a little deeper, and not all is right. As you read further, be very careful to understand that I am not saying the Cynefin framework is not useful. It is useful. What I am saying is that its construction as a leader’s framework for decision-making is not quite right due to an ontological mix-up. And it can be more useful if it is improved to better reflect reality.

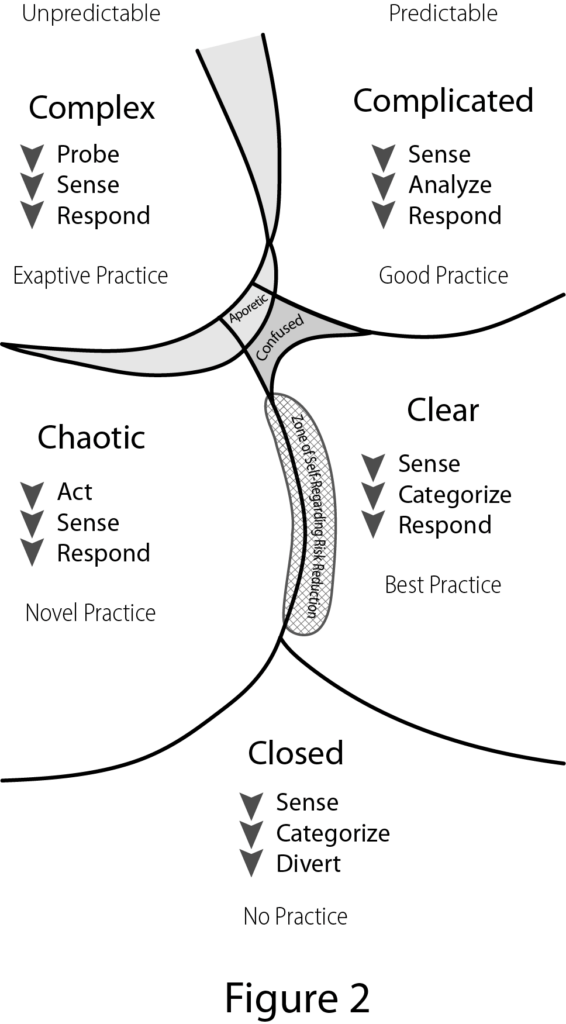

My study of leaders, leadership, and leadership decision-making over the past 25 years leads me to conclude that there is an omission in original and subsequent constructions of the Cynefin framework, one that does not fully represent the reality that leaders occupy. Figure 2 shows modifications that I made to the Cynefin Framework, which I call “Cynefin+1”, reflecting the addition of a Closed domain (first published here). What is the Closed domain? Throughout history, at least since the time of ancient Egypt (5000 years ago), if not earlier, leaders have status (authority and respect), rights (safeguards against interference or fear of repercussions), and privileges (resources and opportunities) whose function is to enable them to fulfill their responsibilities. Those responsibilities can be tilted strongly or weakly towards self or others depending upon the circumstances (needs, complexity, etc.).

Over time, the status, rights, and privileges of leaders have coalesced into what I call the “Institution of Leadership” (an emergent property) — where the word “Institution” means “the social habits of thought and action of a group.” The “Institution of Leadership is an invidious institution whose passion is the preservation of vested interests. And, in a play on W. Edwards Deming’s “System of Profound Knowledge,” I refer to the constellation of leaders’ status, rights, and privileges as the “System of Profound Privilege,” an interlocking system of social power that passes along from one leader to the next via socially inherited traditions. As we all know, the status, rights, and privileges are far greater for leaders than non-leaders. When leaders are confronted with a problem that does not align with their personal or strategic interests they are under no obligation to concede that a problem exists nor are they required to address a problem that they have no interest in. That is a very important part of their reality. The Institution of Leadership and System of Profound Privilege allows leaders to claim, rightly or wrongly, that a problem does not exist or that a problem is not severe.

So, using the Cynefin framework, leaders determine the context of the problem that requires decisions and then follow the specified appropriate practice (Best, Good, Exaptive, Novel). The question is, how do they determine the context? In the case of senior leaders (especially), their preconceptions can unconsciously guide them to determine the context that best fits their personal desires and needs independent (or in spite) of empirical evidence. They will likely choose the Closed domain whenever the problem context clearly threatens their status, rights, and privileges. Leaders can, of course, re-evaluate the context after their initial decision, based on new or old evidence (or not), but most leaders double-down on past decisions to avoid looking weak or indecisive.

The Closed domain depends on the existence of the Institution of Leadership and System of Profound Privilege. To deny their existence, however, is to negate the history (and the massive documentation thereof) of leaders and leadership decision-making, followers’ experiences, and reality itself. That is an unwise, if not silly position to take, but that is what Dave Snowden has done (private communications with Mr. Snowden). If Snowden et al. accept Figure 2, then that changes the ontological and epistemological basis of the Cynefin framework for the worse, in their view. The Cynefin framework could be improved by considering the social, political, economic, and historical contexts that have long shaped leaders’ existence, their thinking, and their behaviors.

In the phrase, “the social habits of thought and action of a group,” what is “the social habits of thought” and who is the “group”? Think of “the social habits of thought” as the culture shared by leaders (an emergent property), which we all know from first-hand experience differs substantially from non-leaders. The “group” can be leaders at any level, from supervisors to mid-level managers to executives, the CEO, and the board of directors. However, for lower-level leaders to survive in their position, they must, to greater or lesser extents, exhibit some of the social habits of thought of their senior leaders.

We have all experienced leaders, from supervisor to CEO, who did not recognize problems that we recognized as important problems. They could do that for a number of reasons such as:

- Not going to the source to see the problem for themselves

- Having a different opinion about the problem or its significance

- Not having the time to investigate the problem

- Not having resources to address the problem

- Not agreeing that there is a problem

- Not wanting to spend political capital on the problem

- Ignoring the problem to avoid its impact on compensation

- Ignoring the problem to avoid its impact on status and reputation

In most organizations, problems are generally seen as bad and that problems reflect poorly on leaders’ abilities. Problems, even small ones, are often socially unacceptable in hierarchical organizations. Consequently, leaders have a tremendous motivation to avoid problems or deny their existence. Whether they are pushed to see the problem or not, the easiest and fastest way for leaders to avoid or ignore a problem, or to claim the problem does not exist, is to invoke their status, rights, and privileges. Hence, the Closed domain shown in Figure 2. The leader’s response to certain problems will be to Sense (e.g., recognize something as distasteful), Categorize (e.g., extent of the threat), and Divert (e.g., direct people to focus on something else or create a different problem, perhaps one that does not exist). In terms of Divert, people will typically do what the boss says — for example, focus on something else — and the problem facing the leaders has now been solved!

Notice in Figure 2 another change to the Cynefin framework, the elimination of the Cliff and addition of the shaded region denoted “Zone of Self-Regarding Risk Reduction.” What does this mean? The “Zone of Self-Regarding Risk Reduction” represents opportunity for leaders, not misfortune. For senior leaders, and especially CEOs (and political equivalents), the phrase “Don’t let a crisis go to waste” comes to mind. Whether the crisis (Chaotic domain) is self-inflicted or not, there is an immense opportunity for the leader to get creative (Novel Practice) to simultaneously manage the crisis while reducing personal risk, invariably with the full support of the board of directors. Leaders can do this because they have the opportunity via their status, rights, and privileges to create a favorable (or less bad) outcome for themselves, often at the expense of others, and they have resources, the support of the board, the support of subordinate leaders, and the support of external peers.

This contradicts the representation of the Cliff in Figure 1 (liminal line between the Clear and Chaotic domains) as always being misfortune. Instead, leaders often turn crisis into opportunity for themselves and others (Figure 2). In corporate leadership today, senior leaders often fail upward or land solidly on their feet elsewhere. It is the custom in the Institution of Leadership to take care of one’s peers, knowing well that the favor will soon be returned.

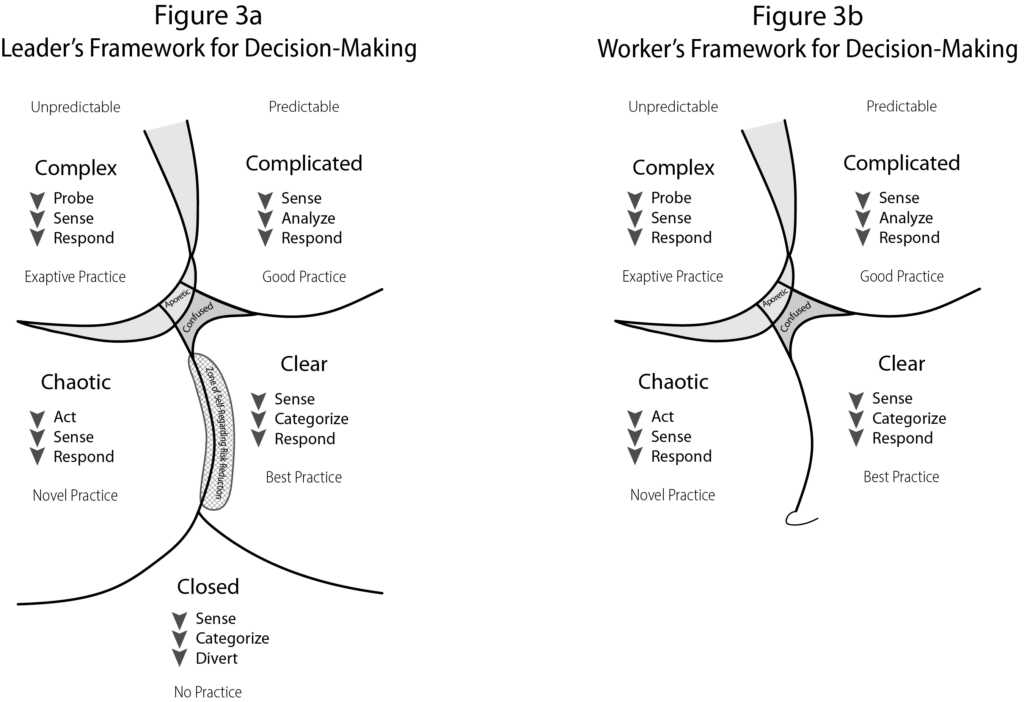

The consequence of all this — which is purely a reflection of reality — is that Cynefin must be split into two different frameworks, one for leaders and one for workers, to correct the ontological mix-up embedded in Figure 1 (and extending back to all prior versions of the Cynefin framework).

Figure 3a is a leader’s framework for decision-making, reflecting the reality that leaders have the status, right, and privilege to ignore problems (Closed domain), from supervisor to CEO. To what extent leaders exercise their status, rights, and privileges depends on the context of the situation, the gaps in knowledge that they are willing to live with, and the professional and personal risks they are willing to incur.

Figure 3b is a worker’s framework for decision-making, reflecting the reality that workers do not have the status, right, and privilege to ignore problems. Of course workers can ignore problems, but it is not based on them having status, rights, and privileges. It is instead an artifact of leaders’ status, rights, and privilege to ignore problems. It is part of the culture of the Institution of Leadership that filters down to workers throughout the organization. The words “If the boss doesn’t care about the problem, why should I?” should be familiar to everyone.

Two Cynefin frameworks are necessary because the nature of reality and the lived experiences of leaders differ substantially from the nature of reality and the lived experiences of workers as they go about doing their complementary activities. This is not a simplistic worker-leader dichotomy, nor is it a Manichean (good vs. evil) dualism. It is instead an analytical tool (a methodology) used in the style of Veblen to discover and explain previously unseen, or seen but much under-appreciated, system dynamics. The two frameworks, reflecting the presence and absence of Institution of Leadership and System of Profound Privilege, expose a common type of cyclic doom loop that serves no one’s interests. It highlights the perpetual reality in organizations, that certain problems which should get solved do not get solved, and that dissatisfies and frustrates both workers and leaders (and customers), with each thinking the other is, to some degree, incompetent and uncaring (read typical example here).

Finally, one can ask: “Is the Closed domain necessary? Can’t leaders apply the logic of the Closed domain to the Clear, Complicated, Complex, and Chaotic domains?” No, because the context for the existence of Cynefin (Figure 1) is action-oriented — for leaders to acknowledge the existence of problems and make decisions about problems with the wholesome intent to correct problems. By fiat, however, leaders will deem some problems are not subject to problem-solving. Where do these problems go, if not into the Closed domain?

PART 2: Let’s look at a practical example of leadership decision-making: Lean transformation. The mission of the Lean movement is to persuade top leaders to abandon archaic classical management and transition to progressive Lean management, which is based on the Toyota Production System and the Toyota Way, more distantly its progressive predecessors early 20th century Scientific Management and late 19th century Systematic Management. To achieve that, Lean promoters and influencers have, over the last 35 years, spearheaded efforts to research and write stories about successful Lean transformations. Over that time, a large body of empirical and theoretical literature has been developed to prove the wide-ranging benefits of Lean transformation to all stakeholders: employees, suppliers, customers, investors, and communities. Competitors benefit as well by having to put in the effort to keep up with their peer companies.

The knowledge accumulated has been used to train people in Lean principles and practices. Tens of thousands of people worldwide work in all industries as Lean professionals. Lean promoters and influencers, in tandem with Lean professionals, put forth the logical and factual arguments that Lean management and associated leadership routines are a better way to lead an organization. Yet, to this day, there have been few enterprise-wide Lean transformations. Most top leaders, when faced with the problem of how to better lead and manage the organization, dismiss Lean management. Top leaders possess the status, rights, and privilege to dismiss the both the problem and the logical and factual arguments for Lean management (Closed domain, Figure 3a). They do this in part because they clearly recognize that Lean management will diminish their status, rights, and privileges. Additionally, Lean transformation is seen by leaders as a Complex problem (requiring “foreign” Exaptive Practice) that can quickly turn into a Chaotic problem (requiring “unknown” Novel Practice) to solve the problem. Most leaders do not want that.

Nevertheless, top leaders must still contend with the ever-present problem of how to better lead and manage the organization. So what do they do? They sense the problem as being in the Clear domain (Best Practice) and the Complicated domain (Good Practice). They make the decision to direct others in the organization to do the things that most other top leaders approve of doing. They use the tried-and-true CEO Playbook, which includes the usual things such as: training programs, hire new managers, cut costs, change incentive compensation, digitize, develop new products and services, raise prices (or lower prices to increase sales volume), outsource or offshore work, consolidate operations, make acquisitions, redesign the organization chart, etc. All of these actions are relatively easy to do and can be delegated almost entirely to internal personnel and external consultants. In doing these things, the top leader can rightfully claim that they are at the forefront of how most organizations are led and managed. They are comfortably one with the herd; no controversy, no inquiries, no explanations. Perfect.

For workers and others, such as the Lean professionals, who are dissatisfied with the status quo, the problem for them is that their top leader is not interested in Lean transformation. What the top leader is interested in is for lower-level people to use certain Lean tools to help them solve the kinds of problems that they encounter when running the processes that produce goods and services. Leaders approve the use of Lean tools for running the workers’ processes, but they reject Lean management for running the business. So what do the Lean professionals do? To them, the problem will likely appear as Simple (Best Practice, Figure 3b), just tell the leader how much more profit Lean management can deliver. Give them the business case for Lean. Or, knowing from experience (or history) that argument rarely works, they will instead view the problem as Complex (Exaptive Practice). Lean professionals, as well as top Lean promoters and influencers, have little to show for 35 years of experimenting with Best Practice and Exaptive Practice. That puts them and their problem into the Aporetic and Confused domains, lacking any potential solutions to the problem they face given their current state of knowledge. With new knowledge, they may be able to do better.

This example, while specific, is representative of many examples of the type where leaders, for whatever reason, do not want to recognize the existence of a problem or its severity. As goes the leader, so go the followers. This is consistent with objective political and business history and subjective lived experience (the intersection of ontology and epistemology). It therefore supports splitting Cynefin into two different frameworks as a pure reflection of reality.

In conclusion:

- The Cynefin framework describes the technical basis for leader’s decision-making, but is deficient in that it trivializes the sociological basis for leader’s decision-making

- The Cynefin+1 framework evinces the sociological basis for leader’s decision-making

- Cynefin is two frameworks, one for leaders and one for workers

- The original Cynefin framework is better suited for workers

- The leader’s framework for decision-making (Figure 3a) can partially or fully disable worker’s framework for decision-making

- The leader’s framework can be used as a tool by trainers and consultants to identify and meliorate “running the business” risks and hazards to one’s self, the organization (including legal liabilities), and employees.

- The worker’s framework (Figure 3b) can be put to much greater use by workers for more effective “running the process” problem-solving.

I expect Mr. Snowden will severely criticize this post with a prickly bramble of erudition (dysgedig in Welsh) or in perhaps in just plain terms. Though I am not sure Dave cares so much about this now-old framework any longer. Based on his recent comments, he is more interested in the scientifically dubious (i.e., replicability problem; discredited nudge theory) but more commercially vendable Estuarine Mapping. Though, we note that human systems (organizations) do not behave the same way as physical systems (objective-subjective derailment), while the question, “where are we?” clearly depends on one’s status in a social hierarchy (knowledge-reality twining). Overall, there is an emphasis on similarities between human-physical systems while minimizing or negating differences. Like all such efforts to improve human social interaction in hierarchies or otherwise, for whatever the reason or end, it is good only so far as it goes owing to pitiless realism. As is usually the case with these types of solutions, the positives are interminably emphasized while constraints, limitations, cautionary declarations, warnings, and the like are invariably unclear or missing. Dave’s criticism of my analysis falls apart because it rests entirely on his denial of the existence of two things: 1. A culture that is unique to people in senior leadership positions (the Institution of Leadership) and 2. The rights and privileges that are unique to people in senior leadership positions (System of Profound Privilege).

UPDATE, 26 December 2023. This blog post was posted on LinkedIn on 25 December 2023. True to form, Dave has done as expected, offering on 26 December the weakest of defense possible. His comment reads: “You’ve been pushing this off and on for over a year now and it’s still as confused as ever, still as driven by a weird form of conspiracy theory as ever” (the comment is in reference to the Institution of Leadership and System of Profound Privilege). It’s been less than a year, actually. The logic of my argument about the Cynefin framework has never been clearer. Absent a cogent counterargument, willful ignorance is Dave’s right and privilege! Snowden later states, “[Cynefin] attracts people trying to piggy back [sic] on the brand. This is one of those.” This is a mistaken imputation. A cursory reading would reveal the blog post as criticism of Cynefin, not as wanting to “piggy back on the brand.” Unlike Dave, I have no desire to engage in the “market of magic tokens” as my large body of work amply reveals.

UPDATE, 30 December 2023. The Closed domain reflects “No Practice.” In particular, problems that leaders do not wish to acknowledge or solve owing to their status, rights, and privileges. Anyone working in an organization for many years notices that certain significant problems exist which go unnoticed (usually deliberately) or unsolved, often across generations of top leaders. What are some real-world examples of problems that leaders do not wish to acknowledge or solve and make the decision “No Practice,” often to the short- and long-term detriment of the organization and its stakeholders? They can include: Organizational politics, of the type that interfere with strategy execution. Low employee morale due to a toxic workplace culture whose tone is set by the top leader. The persistent 30% pay gap between men and women. Workers cite quality problems that will negatively impact schedule and cost (think Boeing 737 Max), and the top leader ignores their warnings. Employees blow the whistle on financial fraud (think Enron, Wells Fargo) and the leaders ignore them or fire them. The price of raw materials goes up 50 percent and the CEO tells the manufacturing vice president that costs cannot increase. Workers begin the process of unionization, but leaders fire them, thus ignoring the underlying problem of why workers want to unionize. Everyone knows about the destructive psychopaths in leadership positions, yet the top leader refuses to part ways with them. You can surely think of many more examples of “No Practice.” The existence of the Cynefin framework is an attempt to correct the “No Practice” right and privilege that leaders possess owing to their status. Cynefin, seeks to get leaders to make anything other than a “No Practice” decision. Yet, as a technical sense-making framework, whose intent is an intervention of some kind, Cynefin necessarily trivializes the sociological basis for leaders’ decision-making in whole or part, and it thus abridges leaders’ rights and privileges. The Institution of Leadership and System of Profound Privilege has its own unique framework for decision-making, free of any abridgment.

UPDATE, 13 February 2024. Here is an interesting example of the nonsense that is produced using the survey methodology in The Cynefin Company’s SenseMaker®product. Image source. The results inconsistent with business, management, and leadership history. The survey results clearly suffers from the problems of inherent to all surveys: a) leading questions and b) respondents answer the questions as they think they should be answered (in this case, social bias, recall bias, and status/ego bias). This is evident in Figures 4-9 and 11-13. Surveys typically suffer from bias and dishonesty. So I question the validity of the results and thus do not see the value in the method. I’m sure participants have a good time and gained some insights, but when they return to work it is likely that little will change. It seems to be yet another example of selling magic tokens dressed up as rigorous science — the current version of Myers-Briggs Type Indicator, likely to be discredited in 20 or 30 years if not sooner.

UPDATE, 27 February 2024. This video features a discussion and critique about the Cynefin framework.

UPDATE, 24 March 2024: Visual description of the Cynefin+1 framework.